Under Pressure! (Part 1)

A flying club's new plane holds an unfortunate surprise

About a year ago I started a flying club at my local airport with three other pilots – that was a long and interesting process that I won’t go into here – but after a few months of trying to get the right people together then struggling to buy an airplane in a hot market, we were able to purchase a 1965 Cessna 172 F with the Air Planes 180hp Lycoming O-360-A4M upgrade, with about 1300 hours SMOH. The pre-buy inspection went well and I had the honor (with another member) of flying our new ship home to Illinois from Florida.

As a 12-year analyst at Blackstone Laboratories, of course I did an oil and filter analysis as part of the pre-buy inspection. With that data in hand and considering how active our new aircraft was, we decided to proceed with Lycoming-recommended 50-hour oil changes right off the bat.

The first few oil analysis reports were excellent, and the oil filters came back nice and clean. The first time we pulled the oil suction screen we found a small amount of fibrous material in it, but the previous owner confessed that they hadn’t ever pulled the screen, so we assumed the debris was probably years – if not decades – old. We didn’t worry too much about it. When the next screen came back clean, save for a mere spec of carbon, we forgot about the fibrous debris entirely and happily went about enjoying our new bird.

Lost oil pressure

That is… until March 29th, when one of our newer student pre-solo members texted that, 10 minutes after takeoff, the engine lost oil pressure. He and the instructor landed without incident and reported everything looked ok, hoping it was a bad gauge.

The questions from the other partners streamed in: where were you? How was the engine running? How was oil temperature? The student pilot clarified: they took off to the north, climbed to 5,000’ to work on maneuvers, and when they did the cruise checklist they noticed the low oil pressure. He reported returning to the airport immediately with no issue. The engine ran great the whole time, and oil temperature was fine. No apparent oil loss.

I was out having coffee with a friend at the time, but my heart sank and I couldn’t focus on anything else, so she and I ended up going to the airport, with an A&P friend on the phone to look for something obvious, like an oil leak at the oil pressure gauge or where the line comes through the firewall. I didn’t find anything, but I wasn’t too discouraged: I knew we had a lot of things to troubleshoot before suspecting engine damage, so I tried not to jump to any conclusions.

Filter pleats with slimy debris embedded

Initial shock and investigation

The following day, our club maintenance director – under the watchful eye of our A&P – started working through the troubleshooting list. We quickly determined it wasn’t the gauge, and it wasn’t the line, so the easy, cheap fixes were off the table.

Now concern was starting to mount; the deeper we had to dig, the deeper our pockets were going to have to be. We’re a new club, already operating on a shoestring budget, so we didn’t have time or money for costly repairs. But we had a problem to solve.

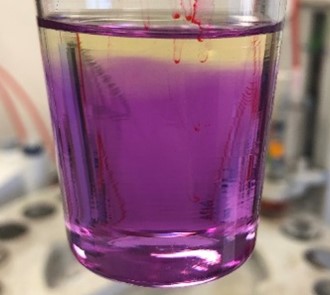

The next step in our troubleshooting process was to start looking for a problem. We drained the oil, pulling an oil sample in the process, and we removed, cut, and inspected the oil filter. The only abnormalities were some clumpy, slimy looking lumps (see figure 1) and a giant piece of carbon (figure 2). The carbon was large enough to wonder if something similar had gotten stuck in the oil pressure relief valve, so we pulled the oil pressure relief valve off hoping for a big piece of carbon to be our easy culprit.

Much to my dismay, the oil pressure relief valve was totally clean.

Looking at the screen

Later that night, with the oil drained, the filter cut and the oil pressure relieve valve not the suspect, I pulled the oil suction screen. My heart sank. The screen was completely blocked by fibrous

Debris on the end of a fingertip

material. It looked like the same stuff we found in our earlier oil change, only a whole lot more of it. The pickup screen was so caked full that I had to use a screwdriver to pry the debris out of the screen (figures 3a and 3b).

That’s when concern really started to set in: we actually did lose oil pressure, and there could be some serious damage here.

A few days later the oil analysis and official filter report came back: the oil report was unremarkable, but the oil filter report was disheartening. Our engine had gone from making “no appreciable metal” in 50-hour oil change intervals to making “non-ferrous metallic flakes at an approximate rate of 20 pieces per filter pleat” in a matter of 20 hours. Great. Now what?

Fact-finding

The filter report stirred up more questions than it did answers. The next step in the process was to figure out how much damage was done, what that fibrous material was, how it got there, how much remained, and, most importantly, what to do next?

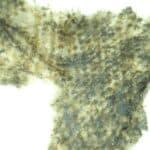

The fibrous material turned out to be the easiest question to answer – it was a paper towel. When examined under a microscope, it had the very distinctive dimpled pattern you see on “quilted” paper towels (see figure 4). Once we identified the contaminant, the next step was figuring out how it got there.

Fluffy stuff that came out of the suction screen

Interestingly enough, the previous owners provided the answer in the photographs they shared with me during the pre-buy. A couple of photos showed the process of swapping the original O-300 with the O-360. In figure 5 you can see a couple of paper towels sticking out the back of the engine where the magnetos should be. I believe that some (or all) of that paper towel somehow ended up getting stuck in the engine – either someone turned the prop and the gears pulled it in, or some of it got wet with engine oil and broke off into the engine.

You did what?

There’s another interesting twist to this story: as we were trying to figure out how long the engine ran with no oil pressure, we looked at the flight track on FlightAware. As reported, the plane took off to the north, climbed to about 5,000’ turned around then did a 360’ turn, presumably to lose altitude. Then there’s a normal approach to landing and…a go-around.

Wait, what?

That’s right – a go-around. With no oil pressure measuring on the gauge. When we confronted the CFI about the flight track, he confirmed: the student pilot was flying, and he came in too high and too fast to salvage the landing, so a go-around was initiated. *face palm*

Why didn’t the CFI take control of that flight and land? Because he assumed it was a gauge problem. Oil temp was fine, the engine was running well, so he didn’t worry about it.

Ground up paper towel under a microscope

The good news was that the CFI confirmed that oil pressure wasn’t lost entirely (as the student pilot had reported). It was only lost when at idle. If there was some power, there was some (albeit not much) oil pressure reading on the gauge. With that information, and knowing the engine hadn’t seized entirely, we were hopeful the engine damage was limited.

Moving forward

So, we’ve finally found the culprit, and now the long road to recovery begins. The main takeaway from this part of the story is, if you see anything unusual at all – anything – get on the ground as soon as possible. Don’t assume a low oil pressure reading is a bad gauge, and don’t fly when something might be wrong. Don’t dilly-dally, waiting for traffic to clear. Declare an emergency if you have to and diagnose with two feet firmly planted on terra firma.

Check back in the next newsletter as we discuss the confusing, gut-wrenching process of figuring out whether we could salvage the engine!

Related articles

A New Wave

Saying goodbye to my 1984 Chevy

TBNs & TANs: Part 2

Determining how heat affects the TBN and TAN of the oil

Finishing the RV-12

The last article in our series on finishing the RV-12

In the Thick of it!

Five cities, five days, 5000+ cars: the 2024 Hot Rod Power Tour!