40 Years of Testing Aircraft Oils

This summer marks our 40th year in business, so we thought it would be interesting to have a look back at our history in the field of aircraft oil analysis and how we got to where we are now.

Jim Stark (my father) was first introduced to flying as a teenager by getting a ride in a surplus P-51 owned by local legend Denny Sherman – talk about a fantastic Young Eagles ride! After that

ride, Dad was hooked, but it wasn’t until the early 80’s that he actually started chasing the dream of getting his pilot’s license.

Shortly after he got his license, he was fired from his job working with a local diesel fuel additive company and started working on Blackstone that same day. The funding for this company came entirely from debt, which meant he had to work hard to make ends meet with the family, and all non-essential expenses went right out the window. So long, 1972 Jaguar XJ6 with a bad head gasket, so long kids’ college fund, and so long flying.

Still, he had the flying bug and decided right away that Blackstone would support to aviation community by testing aircraft oils, not to mention he really needed the revenue. There are a lot of oil analysis labs out there, but only a handful test aircraft oils. There is a certain amount of knowledge you must have to test these oils correctly and deal with the challenges that come along with handling samples that are chock-full of lead. Along with being passionate about aviation, Dad had graduated from Purdue University with an Aviation Technology degree and A&P license, so the knowledge part came as second nature. He figured he’d learn how to deal with lead on the job.

Early Years

In the early years of Blackstone, we really didn’t test many aircraft oils—two or three a day if we were lucky. He made sales calls to FBOs in the area, but sales were slow. He had a lot more

success focusing on industrial factories and diesel truck fleets, but he never stopped trying to crack into the aviation market. Since this was well before the days of the Internet, they had to get

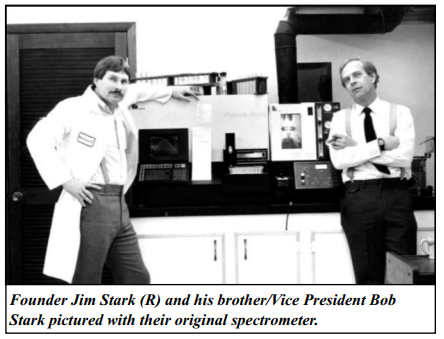

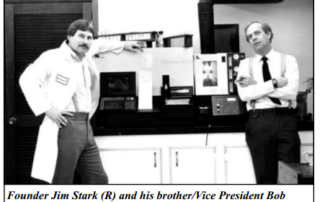

creative in figuring out how to tell aircraft owners and mechanics that Blackstone even existed. One of his early sales efforts was a sample kit mailing program. He bought a list of aircraft owners in Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, and Kentucky from the FAA and sent one sample kit to everyone on the list. Another sales idea he had was the EAA airshow at Oshkosh Wisconsin. The funding to get a booth like we have now was out of the question, so he and my Uncle Bob (company Vice President at the time) decided to drive up to the show. Then they jumped a fence to get in (again, times were tight) and set an oil sample kit on the wing of every airplane they could find. As you can imagine, this type of “shotgun-marketing” didn’t result in a major influx of samples, but considering the fact that we still have customers today from these programs, both can be deemed a success, just a long time coming.

Enter Howard Fenton

We didn’t really hit it big in the aircraft market until 2002. That was when Howard Fenton called us up one day out of the blue and wanted to sell his company to us. He had first heard about us at

Oshkosh when some joker set a Blackstone sample kit on the wing of his Grumman Tiger, not knowing that he also owned an oil analysis company called Engine Oil Analysis (EOA).

EOA had been in aircraft oil analysis since the 1970s and was well respected in the aviation community. He sent in a sample to us to see what we were all about and decided he liked how we reported the results, so when it came time to retire from the oil analysis side of things, he called us to see if a deal could be made.

Jim and Howard hit it off right from the start. Both had worked for Dana for a lot of years and both were pilots, so Jim made a quick trip to Tulsa, Oklahoma to visit Howard, and the deal was done. Howard didn’t actually own a lab, he just contracted a local environmental lab to test his oil on their spectrometer. When they were done, they would give him a text file with the results and he had to hand-enter the data into his database reporting system. So basically, the only thing we bought from Howard was a client list, a bunch of historical data from the samples he tested, and all the goodwill the EOA name carried with it. Fortunately, Howard had roughly 3,000 happy customers, who trusted Howard’s judgement in choosing us as a replacement, so the transition for his customers to our service went smoothly. Blackstone was now a major player in the aircraft oil analysis field and we’ve never looked back.

40 Years of Growth

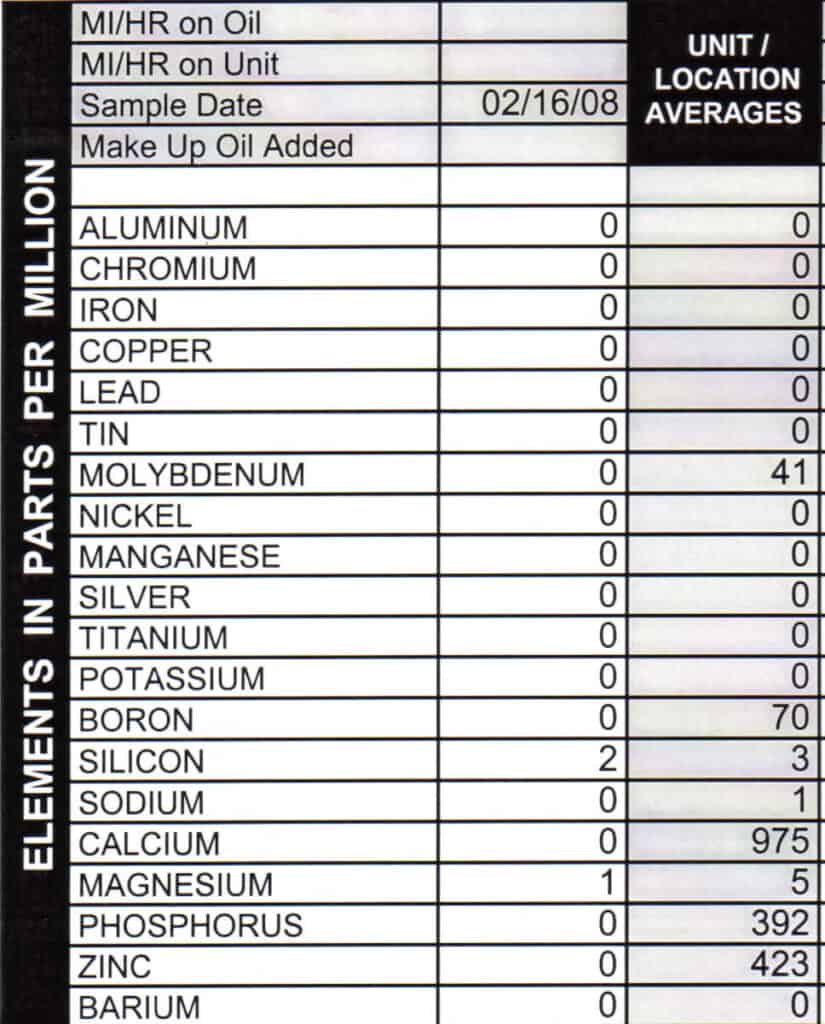

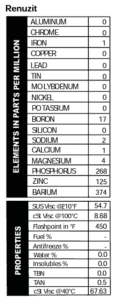

There were growing pains associated with taking on such a large chunk of business. The actual testing of the oil really hasn’t changed much over the years. We still offer the same standard

analysis as we did back in 1985. That includes the spectral examination, viscosity, flashpoint, and insolubles test. Spectrometers have improved significantly since 1985 in their reliability and ease

of use, but the accuracy of those old machines is comparable to what it is today, at least for our purposes, which means rounding to the nearest part per million.

As a lab, we needed to learn how to handle not only the large jump in aircraft samples, but the significant amount of leaded waste oil that goes along with it. Since a lot of the waste oil (including most of what we produce) in this world is burned for heat, and there is a limit to how much lead can be in your waste oil, it became obvious that we needed a separate lab just to handle the leaded oil, so we built one.

We also needed to develop a way to train new report writers. One of the things our customers like about our service as the comment section. It takes people to write those comments and the people we hire don’t tend to know anything about engines, so the training program we developed was extremely important in helping us expand and grow.

After Howard sold us EOA, he created a new company called Second OilPinion. Its focus was to inspect aircraft filters. We had never really wanted to get into the filter testing business. It was our

opinion (and still is) that this is something owners and mechanics can and should do on their own, but that doesn’t diminish the fact that Howard had a lot of people who were sending their filters to him for his opinion on what metal was showing up.

After Howard passed away in 2018, we decided to support the customers he was serving and developed our own filter analysis program. This program has come a long way over the years and we’re working on more improvements like developing a way to determine what alloy of metal is present when we do find a large chunk in the filter.

So, that’s a little history of where we’ve been. In thinking about the future, I am really looking forward to the widespread use of unleaded fuel. I believe this will be a boon to aircraft engine owners from a maintenance point of view. Leaded fuel is dirty fuel and the blow-by tends to be corrosive in nature. Once 100LL is safely eliminated, I predict a lot of problems like fouled plugs and stuck valves will fall by the wayside. From a business side of things, we won’t be able to use lead as a judge of how much blow-by is getting into your oil, but on the plus side, we won’t need to have a separate lab just to test aircraft oils anymore.

This past year we did have some major challenges processing samples in a timely fashion, but those have been addressed and our current turn-around time is back to 5 days. Thank you for sticking with us. We’re looking forward to a great 2025 and beyond.

The boat is a 1994 Starcraft 1700 with a 90 HP Mercury 2-stroke engine. It’s large enough to carry six people comfortably and pull a tube around the lake. She bought the boat used in 2016 and it had obviously not seen a whole lot use or maintenance in the preceding years, so I decided to help out with what little maintenance I could, which basically involved changing the oil in the lower unit.

The boat is a 1994 Starcraft 1700 with a 90 HP Mercury 2-stroke engine. It’s large enough to carry six people comfortably and pull a tube around the lake. She bought the boat used in 2016 and it had obviously not seen a whole lot use or maintenance in the preceding years, so I decided to help out with what little maintenance I could, which basically involved changing the oil in the lower unit.

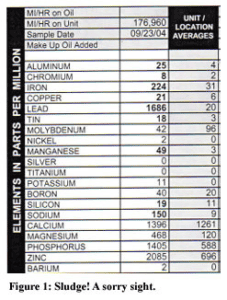

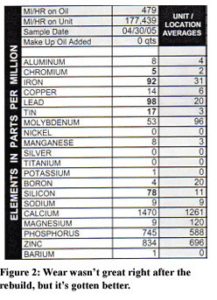

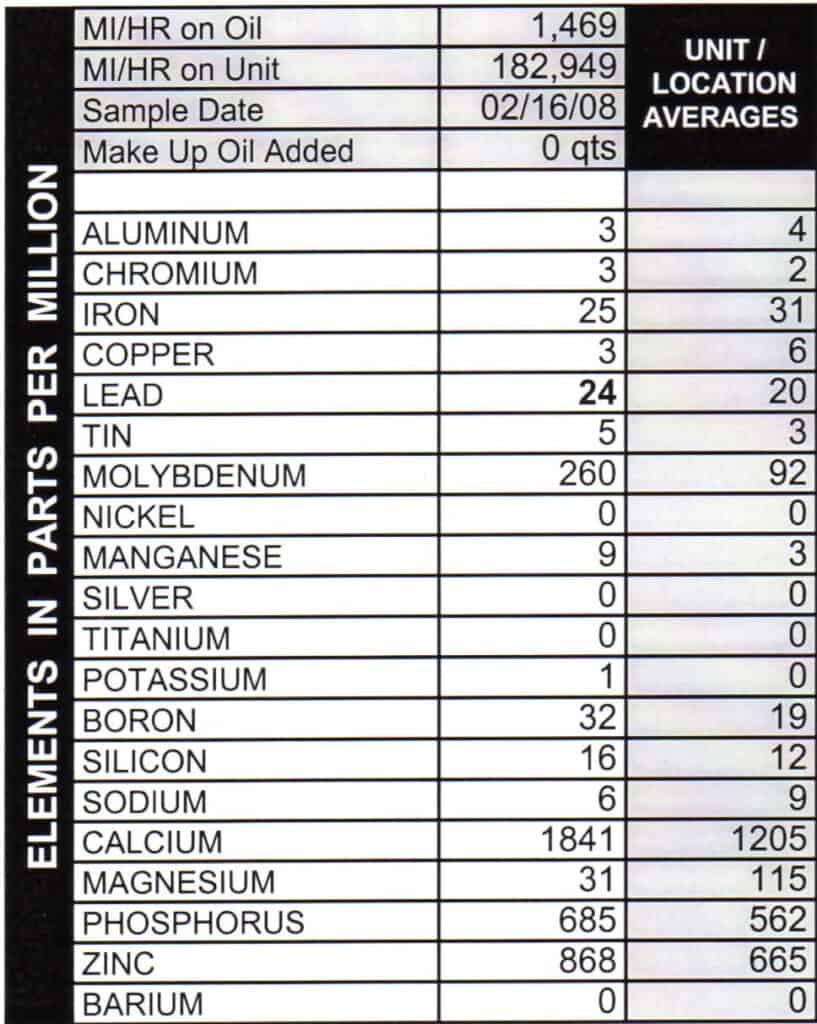

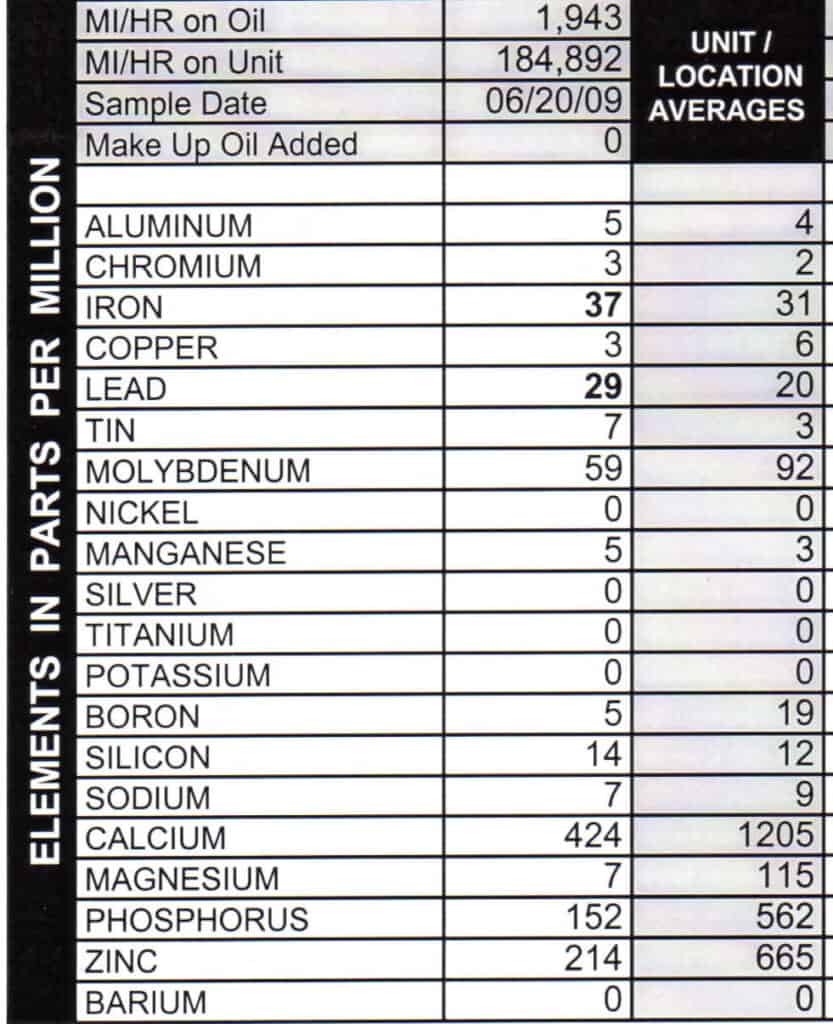

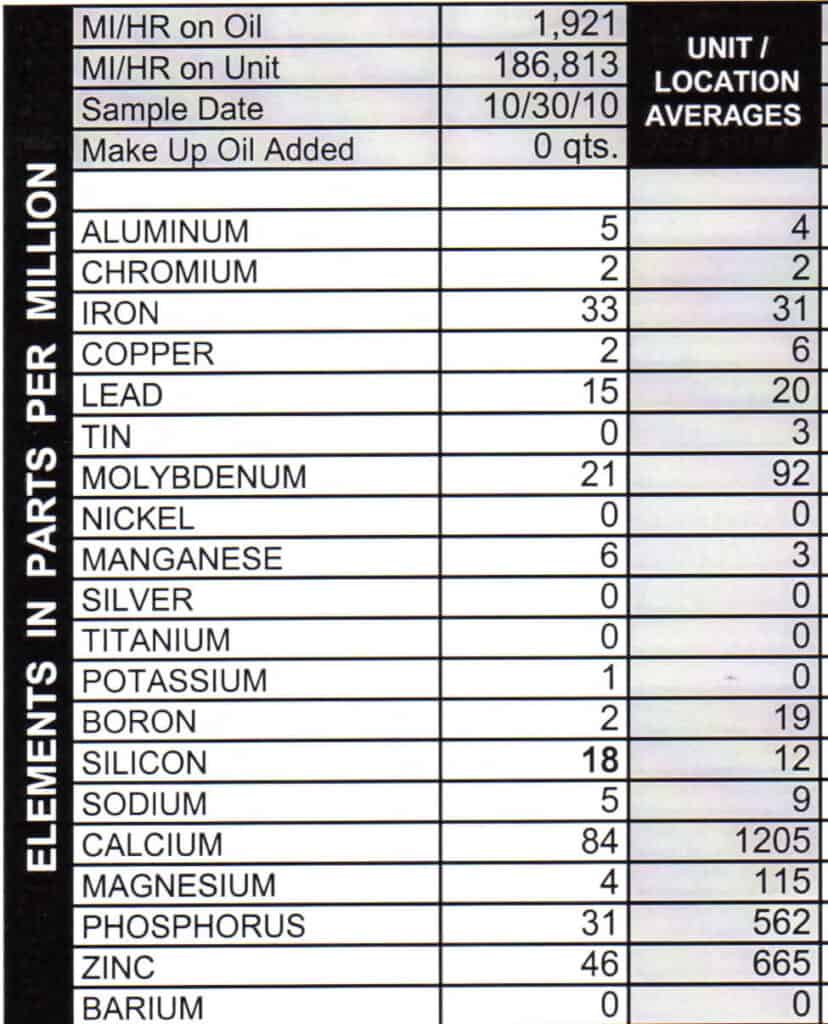

If wear is above average, we always look for reasons that might explain why. For example, say your metals are generally higher than average but you’re also running your oil longer than average. We take that into account and give you an estimate on how much longer we think you can go for the next oil change.

If wear is above average, we always look for reasons that might explain why. For example, say your metals are generally higher than average but you’re also running your oil longer than average. We take that into account and give you an estimate on how much longer we think you can go for the next oil change.