Is Fuel Dilution Just a Hybrid Thing?

A lot of worries pass through our lab each day. Some are warranted, like when knocking or coolant loss ends up manifesting in high bearing wear or coolant contamination in testing. But

just as many worries stem from common misconceptions and when that happens, we’re happy to assuage these concerns. Occasionally, though, a trend will coalesce in our data, seeming to

confirm a common assumption. Today we’re delving into the assumption that hybrid engines are more prone to fuel dilution than conventional ones, and we’ll try to determine whether or not that

should keep you up at night.

A Grain of Truth

A lot of hybrid owners dismiss fuel dilution in their samples, deeming it inevitable for motors working only part of the time. Others are less comfortable with repeated high fuel readings, and

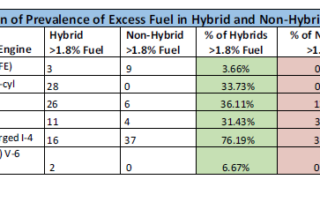

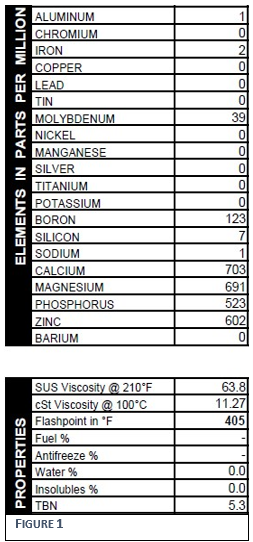

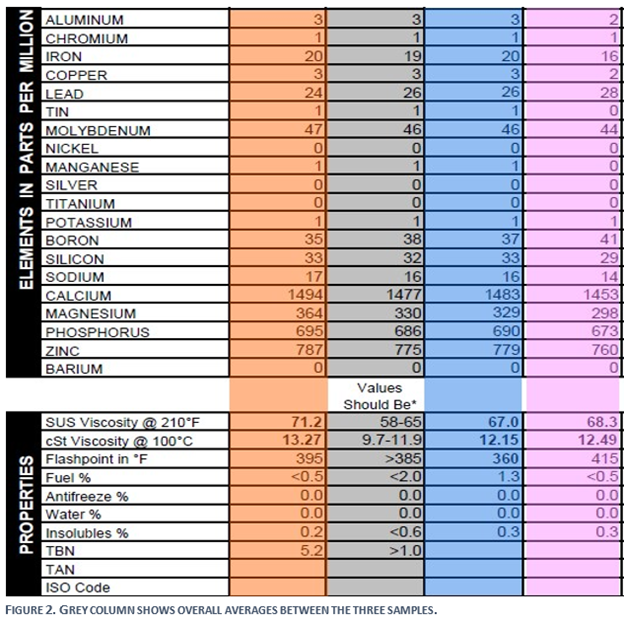

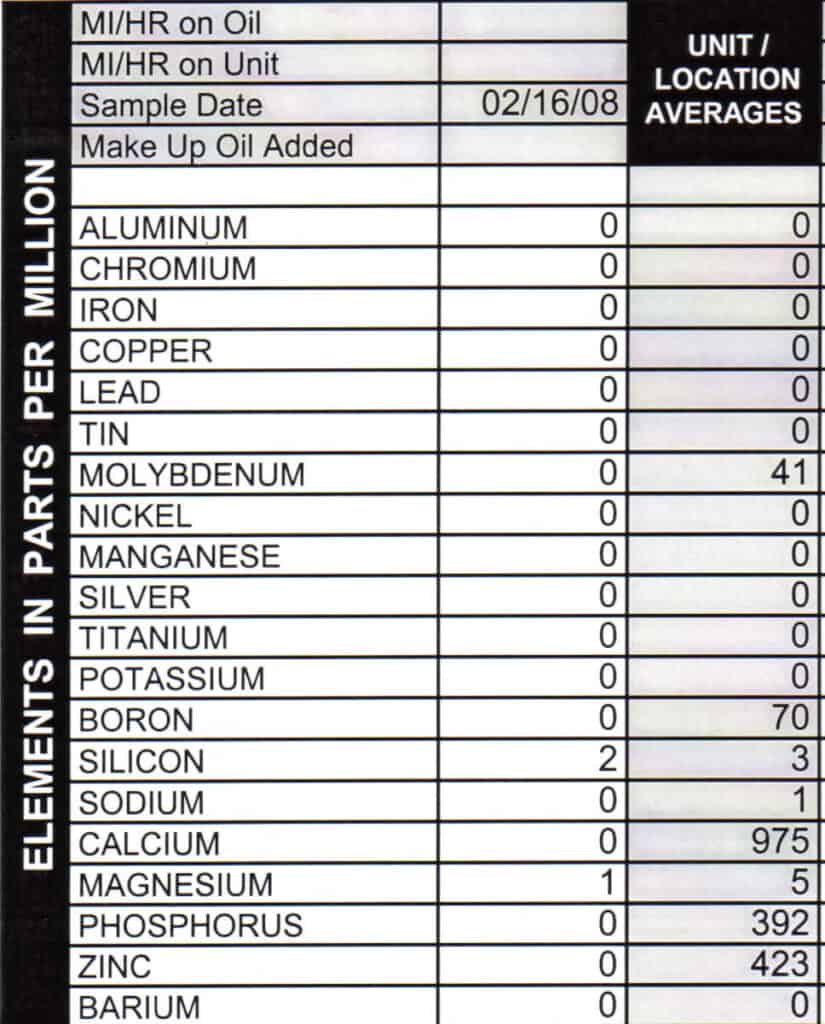

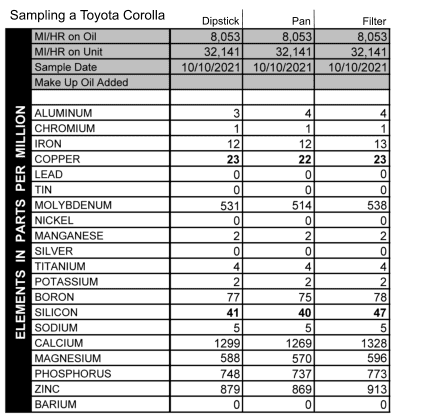

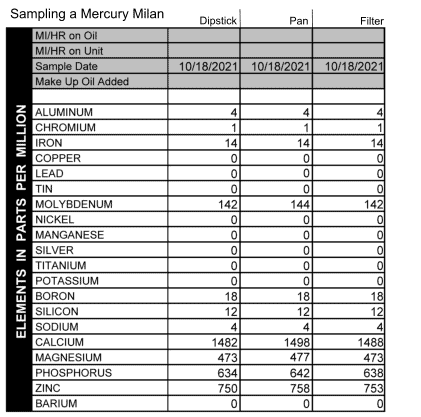

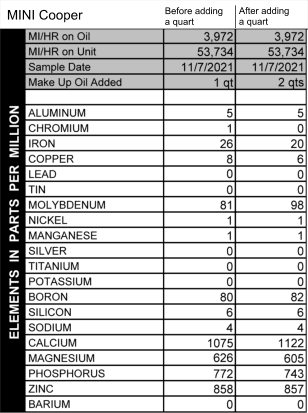

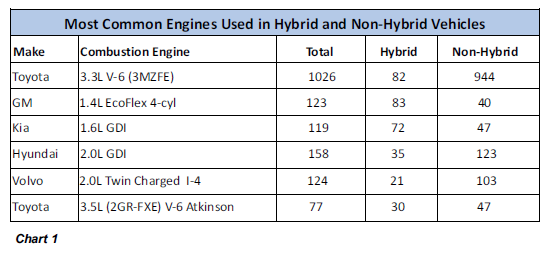

seek advice on how to make it go away once and for all. To address these questions, we started by rounding up six engine models from various manufacturers. These were models used in both

hybrid and conventional vehicles, which also had relatively large sample pools in our database. A breakdown of the number of hybrid and conventional vehicles running these models is shown

in Chart 1.

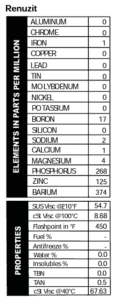

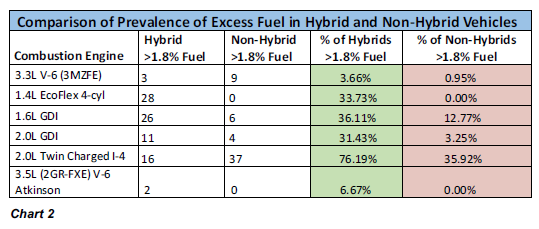

We then recorded how many samples in each group contained 2.0% or more fuel. Anything less than 2.0% we consider fairly benign, but beyond that threshold, we start to wonder about fuel

system trouble. These results are shown in Chart 2.

Some engines ended up with only a slightly higher incidence of excess fuel in their hybrid models, while for others the disparity is quite significant. But on average 31% of the hybrids

contained excess fuel, with only 18% of the non-hybrids, seeming to confirm that hybrid engines are more prone to fuel dilution. Which leads us to the question – what’s so bad about fuel getting

into the oil?

Why Fuel Dilution Matters

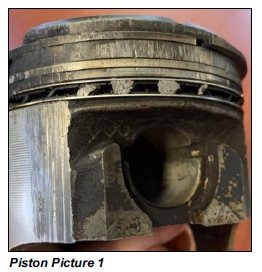

When I brought my findings to Blackstone president Ryan Stark, he shared his own worst-case-scenario. Picture 1 and Picture 2 show a piston from his ’86 GMC Jimmy, clearly in pretty bad shape. Ryan had been dealing with excess fuel for a long while, which started to gum up his oil control rings. This led to the engine burning more oil and the ash leftover from the burning oil left deposits in the combustion chamber. Over time, these deposits got worse and the engine started to suffer from both pre-ignition and detonation. Eventually, the detonation caused a hole to form on the piston, pressurizing the crankcase, and blowing all the oil out the engine. Luckily, he noticed the oil billowing out of the back of the vehicle and the low oil pressure light on the dashboard and was able to pull over to the side of the road and stop the engine before oil starvation caused it to seize up.

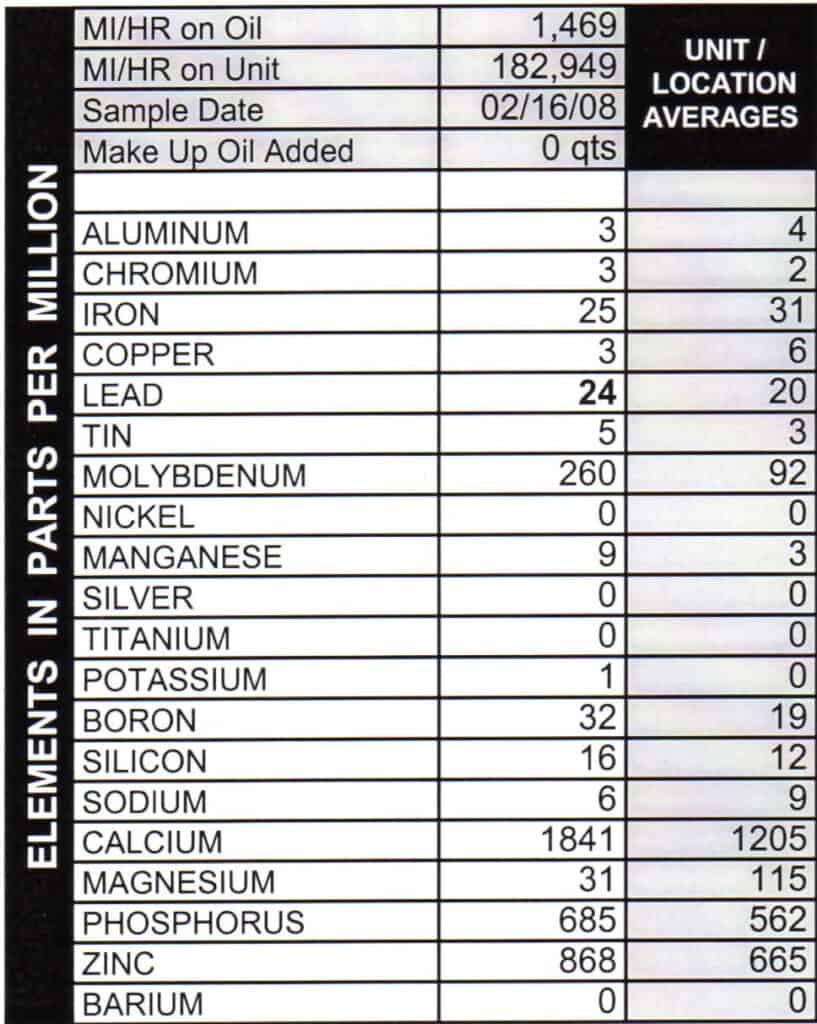

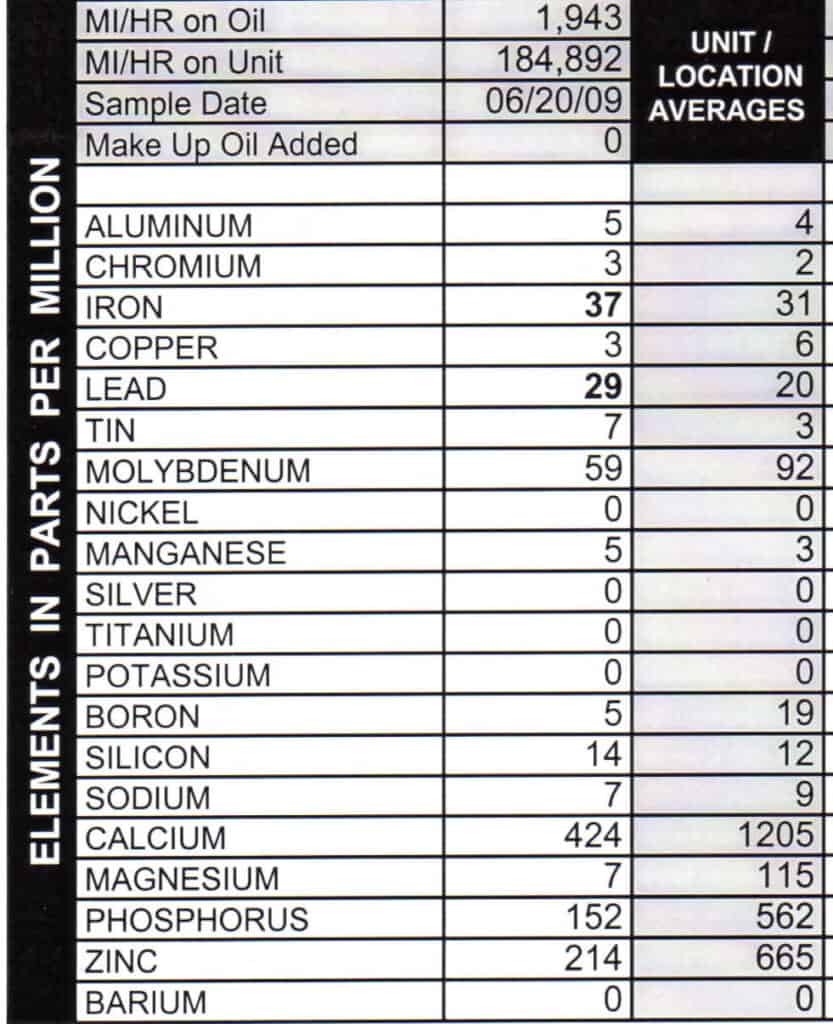

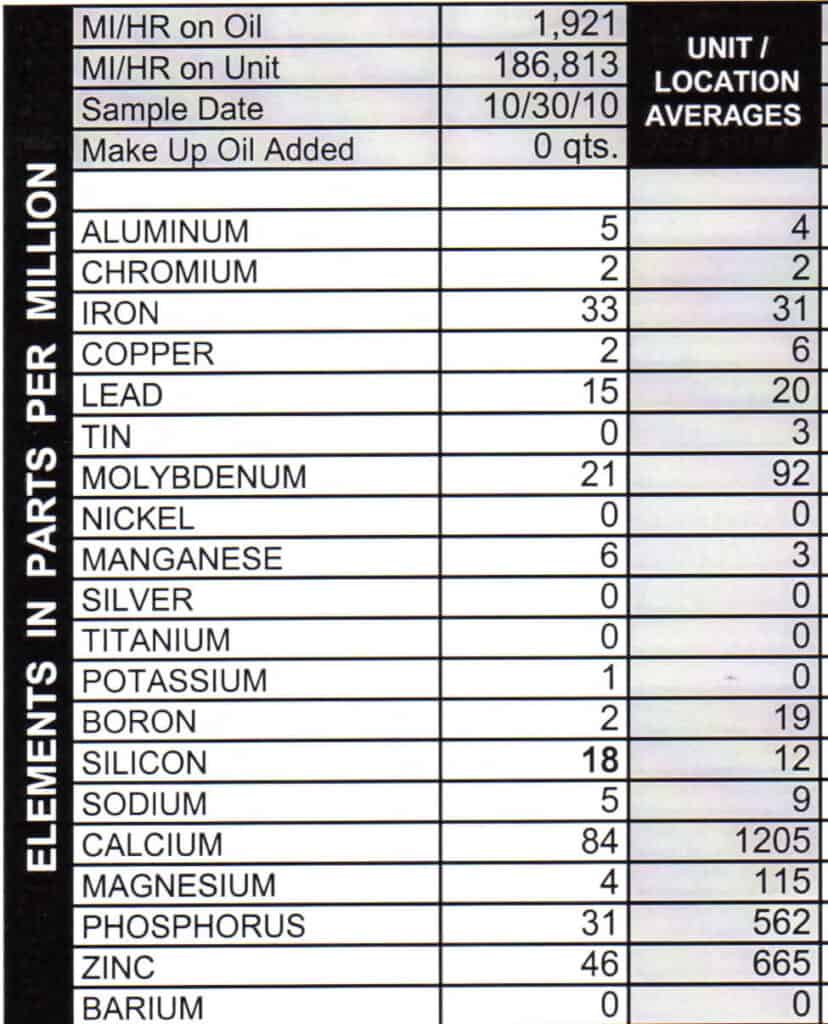

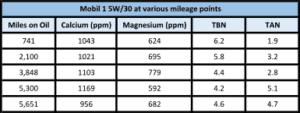

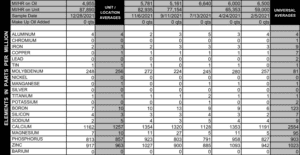

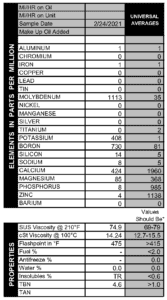

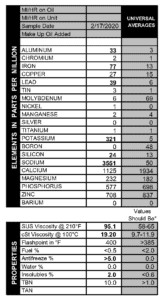

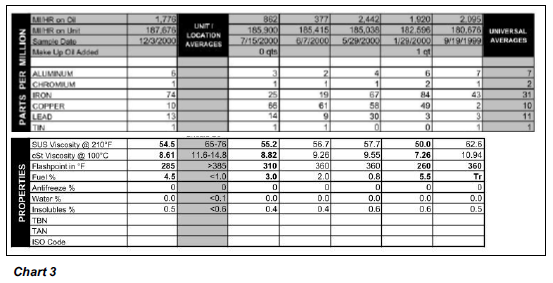

Anyone would want to avoid a fate like this for their engine, so if you find persistent fuel dilution hard to accept, it really only makes sense to try and keep an eye on things using oil analysis. While we no longer have the oil reports from when this problem occurred back in 1996, we do have the last six samples from before Ryan sold this vehicle and you can see the results below (Chart 3). Ryan fixed the piston, yet the engine still had a persistent fuel system problem and the engine likely would have suffered the same fate if the problem was left unchecked. Ryan’s Jimmy was an extreme case. Modern engines are equipped to detect detonation and automatically try to fix the problem by adjusting the timing and fuel mixture. Still, if excess fuel is present, deposits can accumulate over time, but because they line the combustion chamber and form in the ring lands of the pistons, they don’t necessarily show up as wear in the oil. This is why we suggest watching the oil level on your dipstick. If your engine suddenly starts to consume a lot of oil, then it’s possible the oil control rings are no longer working like they should and other engine problems can’t develop. More often than not, poor wear doesn’t go hand-in-hand with excess fuel. A lot of times the fuel actually dilutes metals to such an extent that wear metals actually tend to read well below average, giving you a false sense of security.

After many years of testing oils we are constantly impressed by the resiliency of engines. We don’t live in a perfect world, and fortunately, we don’t have to. At least for a short while, most

engines can withstand some contamination or other mishaps, provided they are addressed promptly enough. That brings us to a couple potential mitigating factors, when it comes to

chronic fuel dilution in hybrid engines specifically.

Hybrids and Fuel Dilution

The combustion engines within hybrid vehicles experience operational factors that traditional vehicles do not. Most notably, they’re continually turn on and off for greatest fuel efficiency. A

hybrid vehicle being used primarily at lower speeds will rely mostly on its electric motor, which is also favored during acceleration. At higher speeds or during prolonged acceleration,

when more power is required, the combustion engine will kick on. This makes for a situation where it’s tough to know exactly how much the combustion engine has been used during a

particular oil run.

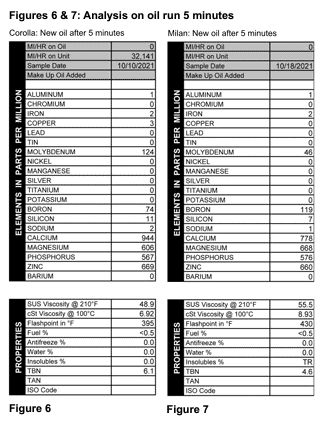

It also seems likely that this sporadic use is a major factor in the prevalence of fuel in hybrid engine samples. Most combustion engines run rich during start up, leading to small amounts of

fuel sneaking past the rings. Whatever ends up in the oil would typically evaporate with sustained engine temps of 212 degrees F. There are a few reasons why this might not happen,

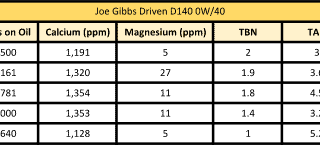

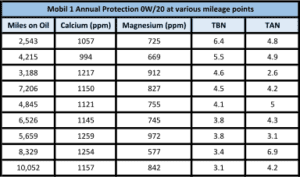

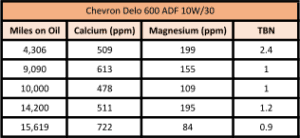

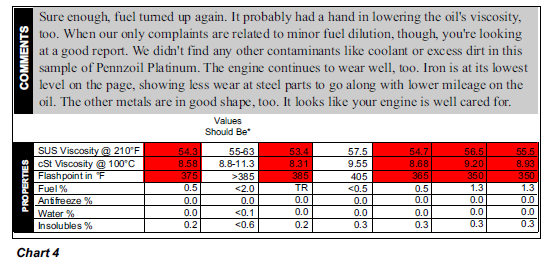

however. Chart 4 is an example of a conventional engine that routinely had small amounts of fuel in its oil, likely due to stop-and-go city traffic. For a hybrid, though, every time the electric

motor kicks on, the combustion engine gets an opportunity to cool back down, leaving any fuel left to accumulate in the oil, rather than cooking out.

Of course, in theory, less use on the engine also means less chance for fuel-related deposits to form. Could the mix of factors impacting hybrids simply balance one another out? From here,

we wanted to answer the burning question: do hybrid engines experience more failures we could associate with chronic fuel dilution? This can be a tricky question to answer directly,

mainly because it relies on customer feedback. Once an engine has failed, it’s not everyone’s instinct to update us on what happened. Then again, some customers certainly do update, and we’ve yet to hear of a scourge of failed hybrid engines for any reason, much less fuel alone. Still, we wanted to see what the hard data had to say about it.

So … is fuel a problem or not?

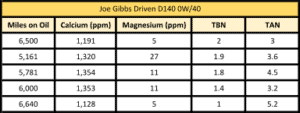

To answer this question, we selected Kia’s 1.6L GDI engine for a closer look. Of the engines shown in Charts 1 and 2, it had the most representative average difference in fuel incidence

between hybrids and non-hybrids. It also had a fairly even amount of hybrid and non-hybrid samples in our system. We then counted samples that had one or more significantly elevated

wear metal. Of the 119 samples, 64 fit these parameters…yet a great majority were simply going through wear-in. Once we eliminated those, we were left with 12 high-wear samples. When we

further narrowed to samples with excess fuel, and separated hybrids from non-hybrids, the numbers became vanishingly small: 1 for hybrids and 3 for non-hybrids.

So, there does not seem to be a correlation between hybrids, fuel, and excess wear, much less premature engine failures. Regardless, it’s obviously better to have less (if any) fuel in your

engine oil; the less contamination, the more the oil is going to function as designed and tested by the manufacturer. So how can we accurately judge the risk, and mitigate fuel dilution, if noted?

Above all, it’s important to monitor the oil level at the dipstick – if fuel dilution is noticeably displacing the oil level, it’s worth inspecting the fuel system, no matter the reason. It’s also worth

making note if your engine is starting to consume oil, since it can be a sign that the oil control rings are no longer working correctly, which could lead to problems with your catalytic

converter as well as pre-ignition and detonation issues. Hybrid vehicle or not, any combustion engine can develop acute fuel system issues that are worth addressing promptly.

But as for the smaller, nuisance amounts of fuel dilution? It never hurts to work the engine a bit harder every now and again, to generate the heat it takes for fuel to evaporate—for example,

hopping on the highway for 15 minutes or so, if that’s not a normal part of your routine. More frequent oil changes can also help to flush out any fuel that’s mixing with the oil, before it can

accumulate to problematic levels. And of course, there’s always oil analysis! We’re happy to help you determine whether fuel is indeed excessive in your engine oil, and help assess what—if

any—action to take if so. Free sample kits are available at: www.blackstone-labs.com/free-testkits.