Unless you rent just one plane a lot, you never really know about a rental plane. You would like to think that it sees careful maintenance all the time, and I’m sure most of them do, but as long as some other person is flying it, it could have problems lurking that don’t show up every flight. Like most pilots, I would like to own a plane someday — something I could fly a lot and get familiar with. Unfortunately, a Republic SeaBee isn’t in the cards right now, so I’ll be renting for the time being. That leaves the possibility for unknown problems lurking that have to be dealt with on the fly (so to speak).

Half power

For me, my first experience with a problem in a rental was actually during flight training. I was flying a Cessna 152 out of Fort Wayne International. I was just going up solo for some touch and go’s and on my first climb-out the engine went to about half power. Thankfully it stayed at half power and I was able to fly the pattern and land without incident.

When I got back in to the flight training building and told my instructor what happened, I got a sense that she didn’t believe me. And sure enough, when we both took it up, everything was fine. She mentioned something like, “I’ll bet there was water in the tanks” (I thought, No, I sumped the tanks and they were clean — I do work in a lab, dammit!) and that’s the last I heard about it. Of course, I was renting the plane, so I don’t know if it had happened before or after my incident, or if something was fixed afterwards that may have been the cause.

In any case, I didn’t panic and made a nice landing (the plane was reusable) so really didn’t think much about it until several years later.

When suddenly…

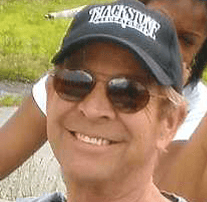

I have had my private pilot’s license for a few years now, and I have been renting a 172N with the Continental O-300. I got checked out in it just fine and had taken a few flights previously by myself. On this particular day, I went up with my Dad (Jim Stark, Blackstone’s founder) and his wife on a sightseeing trip.

We flew north for about 30 minutes looking at the lakes of northeast Indiana, and we had just finished a turn south to head back when the engine started shaking. No little shudder either, but the kind of shaking a dog would make trying to pass razorblades — at least what I would imagine a dog would look like. My dog was never so dumb as to eat razorblades to start with.

Anyway, the engine started shaking really bad. My father (also a pilot) initially said “Get the carb heat on!” and I thought, of course! Carb heat! Continentals are prone to carb ice and I have had nightmares of having to force land an aircraft for just that reason. I’m not sure if I would have thought of that myself, so I was sure glad to have him sitting in the right seat.

I pulled on the carb heat so hard I thought the knob might come off. We sat expectantly for a minute, both waiting for the engine to smooth out. Unfortunately, that didn’t happen. We still had power, but the shaking was bad enough that the thought of a 30-minute flight back to Fort Wayne wasn’t appealing, so I looked at Dad and said, “We’re going back to Angola to land!”

Angola is a town about as close to the northeast corner of Indiana that you can get. It has a beautiful airport with a paved 5,000-foot east-west runway. We were only about five minutes away, but as you can imagine, it seemed to take about an hour to get there.

The carb heat was on the whole time yet the engine never smoothed out, so I figured the engine had some serious issues. The landing was uneventful and as we pulled up to the ramp the engine was still shaking, so we decided to do a mag check.

The right mag check produced no change, but the engine almost died on the left mag. We tested this several times to make sure it was correct and then shut the engine down. One of the best things about the Angola airport is they have an airport car that’s available for situations just like this. It was a late ’90s Ford Explorer that shook almost as bad as the airplane, but hey, beggars can’t be choosers.

I called the FBO where I rented the plane, told them the situation, and then drove home. After an hour’s drive, I pulled into the FBO, gave them the keys and paid my bill. Yes, full price for the time I had the airplane. No discounts for having to make an emergency landing and no allowance for my stepmother needing new underwear. It was okay though, I was just happy to be alive and back in Fort Wayne.

The bright side

Now, the good thing about renting an airplane is, when it breaks, all you have to do is say “Your plane is messed up” and leave. I don’t worry about having to schedule/pay the mechanic, call the people who were renting it afterwards and tell them to make other plans, no hangar fees, no insurance, no fixing knobs that got pulled off.

The bad part about it is that you really never get to know the aircraft and engine ¾ what’s normal operation and what’s not. After a few days, I get a call from the FBO manager who said the engine had a stuck valve. I was fairly amazed because I suspected the horrible mag check denoted something electrical as the problem.

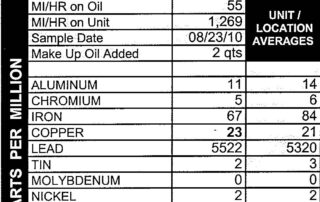

We happened to be doing the oil analysis on this engine, so I checked that to see what it looked like. Aside from a little excess copper, it looked pretty good. However, the O-300 does have bronze exhaust valve guides, so this should have been a warning, at least to be on the lookout for valve problems.

Signs of the problem

Since this incident, I have learned that a really bad mag check is a common symptom of a stuck valve. Some other common symptoms are below.

- Morning sickness — When an engine starts rough first time consistently, not just in the morning, without plug fouling

- Temporary roughness on climb out or in cruise — this happens when a valve momentarily sticks, then shakes loose

- Intermittent rough idle that’s not caused by carb ice (this needs to be ruled out)

If I had been the sole operator of this aircraft, I might have identified some of the other symptoms and put two and two together. Instead, I was not aware of any issues at all. In all fairness, maybe there weren’t any, I don’t know. But I know these symptoms now and I’ll be sure to look for them in the future.

ther Kathy), and plenty of table space. We were also able to bring some parts home to work on in my basement, which was a nice help.

ther Kathy), and plenty of table space. We were also able to bring some parts home to work on in my basement, which was a nice help. It’s a lot easier to walk around the thing without a tail in the way and it didn’t need the tail on until later, when we started stringing the controls for the rudder and horizontal stabilator. I picked up the suggestion while attending a forum at Oshkosh and also learned there that it wasn’t really necessary to complete the sections in order. Things like the rear window installation could be completed after we installed the wiring in the tail section and fuel tank.

It’s a lot easier to walk around the thing without a tail in the way and it didn’t need the tail on until later, when we started stringing the controls for the rudder and horizontal stabilator. I picked up the suggestion while attending a forum at Oshkosh and also learned there that it wasn’t really necessary to complete the sections in order. Things like the rear window installation could be completed after we installed the wiring in the tail section and fuel tank. By the end of 2017, the canopy was on and we were ready to install the landing gear, and this is when we started to outgrow the garage. The problem was that I couldn’t have the vertical stabilizer on and the canopy open with the landing gear on or the canopy would have hit the ceiling. Those items were temporarily removed so we could proceed building, though it became obvious that we would need to move to a larger location soon.

By the end of 2017, the canopy was on and we were ready to install the landing gear, and this is when we started to outgrow the garage. The problem was that I couldn’t have the vertical stabilizer on and the canopy open with the landing gear on or the canopy would have hit the ceiling. Those items were temporarily removed so we could proceed building, though it became obvious that we would need to move to a larger location soon. We see a lot of samples from that engine and they virtually always look great. The big difference between this and other 100 HP selections is that it has liquid-cooled cylinder heads. With that present, it can run either unleaded fuel or leaded fuel, so now I have the option of buying my own fuel instead of always having to buy airport fuel.

We see a lot of samples from that engine and they virtually always look great. The big difference between this and other 100 HP selections is that it has liquid-cooled cylinder heads. With that present, it can run either unleaded fuel or leaded fuel, so now I have the option of buying my own fuel instead of always having to buy airport fuel.