Protecting from Corrosion

The hows and whys of corrosion

Considering the relative inactivity of much of the general aviation fleet, it’s not surprising that corrosion is a hot topic. It’s also fodder for aviation oil makers to claim their oil is better than others at protecting engine parts from corrosion.

The frustrating thing when you can’t find the time to go flying is, your beautiful bird is languishing alone in a dark hangar accumulating rust on its parts and dust and bird doo on its wings. What to do?

If you can’t fly it, you don’t want to just ground-run the engine since it’s pretty well accepted that doing so may cause more harm than good. In the end, the path most often chosen is to “leave her sit.” But that’s the maddening part. You just know that corrosion has begun at the cylinders, cam, and lifters, as well as all the other parts that are parked above the engine’s oil level. “Dammit! Maybe I should go out and shoot some landings.” But you don’t. So the question still stands…what to do?

We get a lot of questions about which oil protects aircraft engines best from corrosion. If there were a sure answer as to which oil is best, someone would surely have come up with it. Since they haven’t, perhaps we should reconsider the question. Maybe what we should be asking is, “What can I do to prevent corrosion in my (not flown frequently enough) aircraft engine, regardless of the oil I use?”

Turned around that way, there may be an answer.

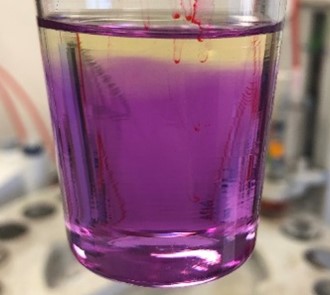

Water orbs

Oil and water don’t mix at the atomic level. Since there is no such thing as dry oil — both hot and cold oil suck moisture from the air like a sponge — the only way these dissimilar types of matter can coexist is for the moisture to ball itself up into minute spheres, so tiny that they can exist in suspension. If the water orbs get large enough they will precipitate, that is, fall out of suspension. But there is almost no limit to how tiny they can be. The longer the oil sits undisturbed, the more water it will accumulate.

Oil routinely has some moisture in it, usually at levels between 40–400 ppm. In amounts greater than that, it can start to make your oil look like chicken gravy. Once moisture sets in, heat and/or pressure are the only way to get it out. If you go out and fly for an hour, the oil temperature and agitation will dismiss the moisture droplets like unruly elementary students. The moisture accumulation process will start all over again once you pull idle cut-off, but at least you have the satisfaction of knowing that, at least for now, the fine film of oil clinging to the metal parts is not heavily populated with tiny balls of water.

Fighting corrosion

After you lock the hangar door, the dry (well, reasonably so) oil film doesn’t last long on all those parts that are parked about the oil level. If your engine is a dry-sump type, none of the parts are parked in an oil bath.

If you can’t fly, you might consider using a pre-oiler once a week to rebathe all the parts in oil. The oil from the pre-oiler will reach all parts that see oil pressure during engine operation. It would require only turning on the master and the oiler switch for a short while, no longer than it takes to check the lights and flaps during a preflight, a few minutes at most. The oil should reach all the way up into the rocker boxes and then drain to form a brief pool over the tappets and cam, parts that are notoriously prone to corrosion pitting in all but the most active engines.

After the pre-oiling dose, you could get out and pull the prop through a few blades (normal direction of rotation, of course) to ensure all moving parts rotate through a couple of full cycles. Further, you will be giving all the rod bearings an oily trip through the sump reservoir, for wet sump engines. (Some people are queasy about touching the prop, so running the starter is an acceptable alternative, if you have confidence in the integrity of the battery.)

Cold dousing all oil-wetted parts isn’t nearly as good as an hour’s flight, but it seems far superior to the ground run-up, or the more often chosen “letting her sit.”

Related articles

A New Wave

Saying goodbye to my 1984 Chevy

TBNs & TANs: Part 2

Determining how heat affects the TBN and TAN of the oil

Finishing the RV-12

The last article in our series on finishing the RV-12

In the Thick of it!

Five cities, five days, 5000+ cars: the 2024 Hot Rod Power Tour!