Sampling Methods

Does it matter how you take a sample?

It’s a perfect spring day. There you are, merrily going about your business of changing the oil. But wait! You forgot the oil sample bottle! A quick scramble to retrieve the bottle gets you back to the oil just as the last of it drains out.

Can you pour a sample out of the filter instead? What if you add a quart a few days before sampling – how does that affect the analysis? What about something like an engine flush – should you use one? Do they work? Your investigative team at Blackstone experimented, and we’ve got answers. While these tests probably won’t qualify for a peer-reviewed journal, they’re a good guide to what you need to know about sampling.

This is part two in our series on sampling methods. Part one, on engine flushes and their effects on analysis, can be found here. Part two covers common sampling scenarios: does it change the results if you take a sample from the filter or dipstick? What if you add fresh oil before sampling? Is it a problem if the oil gets dark right after putting it in the engine? That last question isn’t about sampling methods, but people ask all the time and your investigative team at Blackstone wanted to know, so read on for answers.

Does it matter how you sample?

Our instructions for sampling say to catch a sample as the oil drains from the pan, but that doesn’t always happen. Does it change the date if you take a sample from the filter or pull it through the dipstick?

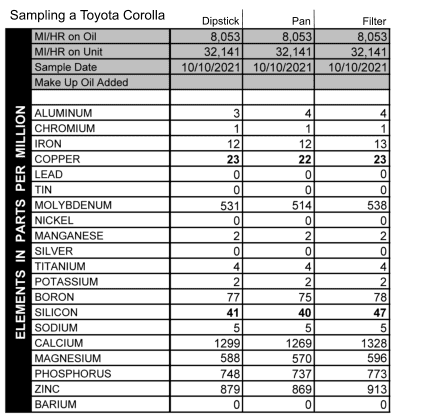

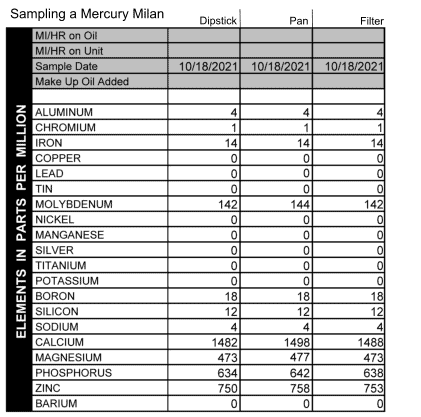

In short: no. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate three consecutive samples taken from two different cars: Figure 1 is from a Toyota Corolla and Figure 2, a Mercury Milan. The column on the left is a sample taken through the dipstick. The middle column was oil taken while the oil drained from the pan. And the right-hand column is oil taken from the filter.

Results

The samples are unremarkable in that there’s less than 1 ppm difference in the wear metals across all three samples. The sampling method seems to have no impact on the metals that show up in analysis.

The Corolla in Figure 1 does show a higher silicon reading in the sample taken from the oil filter, but perhaps that was due to either dirt collected by the filter that ended up back in suspension in the engine oil, or sample contamination – we did have to use a bit of creativity in removing that filter from the engine, as the filter was overtightened and stuck. (If you’re wondering, we stabbed it with a screwdriver to give us more twisting leverage – we did not sterilize the screwdriver before surgery, so it’s entirely possible some silicon was introduced in that process.)

Does adding fresh oil impact the test results?

It makes sense that that adding fresh oil will dilute the wear numbers. But how much do the numbers change? And does it matter when you add the new oil? In theory, if you have a 4-quart sump, adding one quart of fresh oil shortly before the oil change would mean that your engine’s metals are diluted by 25% from their previous numbers.

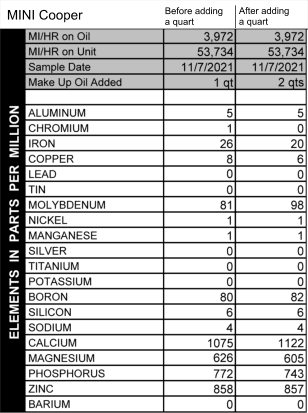

To test this theory, Ryan Stark, Blackstone’s president, pulled a sample from his MINI, then added a quart and sampled again to see how the numbers changed.

Crunching numbers

The MINI has a total capacity of 4.5 quarts, so the one quart he added comprised 22% of the total engine oil capacity. Most of the metals decreased by approximately the same percentage: iron dropped from 26 ppm to 20 ppm (a decrease of 23%), copper dropped by 25%, from 8 to 6 ppm. If we assume that chrome actually changed by less than 1 full ppm, due to rounding, the average change in metal works out to around 25%, which is what we’d expect from adding a quart of oil to this engine.

The only other appreciable wear metal in his sample is aluminum, which, interestingly enough, read at 5 ppm in both samples, showing no change at all. We couldn’t let that element go without a little suspicion – why didn’t it change when the other metals did? As it turns out, the actual number our spectrometer reads goes four decimal places to the right. We round to the nearest whole number on the report, but if we pull the full spectral data from those tests, aluminum read at 5.4290, and in the second test aluminum read at 4.8995. Both readings were rounded to 5 ppm in the report, but the full spectral data shows a slight change between the two samples, an improvement of 9.7%. So aluminum did change with the added oil, just not quite as much as the other metals and not enough to show on one of our published reports.

The “when” factor

There are other variables to consider like how far into your oil change you add the oil, and how much oil you add. If a quart of oil is added at the 3,000-mile mark and you run your oil 10,000 total miles, the dilution factor probably is going to be a lot different than adding a quart just before changing the oil. That’s harder to test for because there are too many variables to isolate.

So this isn’t the be-all-end-all of the dilution question, but it at least gives some insight into the fact that the metals could be diluted if you’re adding oil, especially if you’re doing it right before an oil change. It is a good idea to add fresh oil when low, even if you’ll be changing the oil soon. Running an engine on a diminished oil capacity isn’t great.

Why does my used oil look so dark?

We get a lot of questions from people who do an oil change then notice that their oil is dark immediately afterward. Is it a problem?

To get to the bottom of this question, we conducted two oil changes on two separate vehicles, idled the fresh oil for five minutes, then sampled and examined the new oil.

FIG 4: Toyota Corolla – Left, new oil. Middle, oil after 5 minutes. Right, used oil.

FIG 5: Mercury Milan – Left, new oil. Middle, oil after 5 minutes. Right, used oil.

In both cases, the oils were quite dark after just five minutes of use. In Figures 4 and 5, the virgin oil is pretty obvious, but there’s not much difference between the new oil with 5 minutes on it and the oil with several thousand miles on it. In terms of the overall sample color, it’s quite hard to tell.

Results

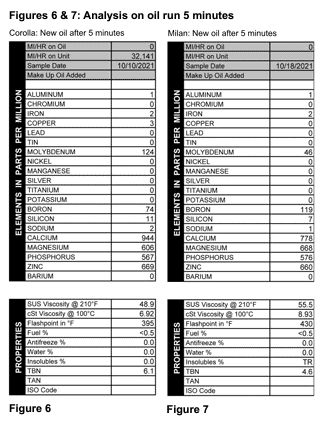

So does the dark oil indicate anything? Figures 6 and 7 show the analytical results of the new (but darkened) oil after being run 5 minutes in two different engines.

Both oils look very clean in testing, with minimal insolubles, no contamination, and very low metal counts. You might note that the metals do not start at 0 ppm – that’s because you never get 100% of the old oil out when you do an oil change. There’s always some carryover from one oil change to the next, and you can see that in the results.

So is it a problem that the oil looks dark right after an oil change? Nope. It’s fairly normal for oil to darken quickly after an oil change. If anything, it seems to suggest that the oil is doing just what it’s supposed to be doing: collecting contaminants and combustion by-products and keeping them in suspension so they can be removed when the oil is changed.

Sampling Methods: Go for it!

In the end, although we give you guidelines about how to sample, your method really doesn’t make too much difference. If you don’t catch a sample mid-stream, just let us know when you send the oil in and we’ll take that into account when we do the analysis. If anything unusual shows up and we think it might be related to something you did, we’ll let you know in the comments.

Related articles

The Price We Pay to Soar

How does the Air Race Classic affect wear?

Landslide!

What size metals can we see? Think of a landslide

ZDDWhat?

An experiment to see if a lack of ZDDP will destroy an older, flat-tappet engine

To All the Oils I’ve Loved Before

What's the best kind of oil?