We were visiting my in–laws last November  and needed some oil for my Passat. It just starting to clatter a little on start up and when I checked the oil, it was down two quarts. The clatter sounded something like “Sell Me” in German.

and needed some oil for my Passat. It just starting to clatter a little on start up and when I checked the oil, it was down two quarts. The clatter sounded something like “Sell Me” in German.

Anyway, while searching for some make up oil (my father-in-law Lee had two quarts of my favorite—Super Tech), I came across an old can of Pennzoil ATF. By old I mean it was a round can made of cardboard, like a Crisco can. It brought back memories of helping my Dad change oil when I was seven or eight. (My job was jabbing the pour spout into the top of the can.)

Lee said he bought it for an old 1984 Buick LeSabre. That was the last car he owned that leaked oil and when that car was gone, he was left with half a can of ATF. Working in an oil lab, I was intrigued by what was in it. So Lee let me have the quart because he would never need it again.

When I got back home, I started looking at old cans of oil on eBay and found a lot. It turns out these are fairly collectable, and I found roughly 300 unopened cans for sale, of all different types and years. I decided that in the interest of science, Blackstone should buy some of these and test them to see what was in them.

Now, you may think I’m crazy because once you open an old can of oil like that you ruin the value of it, but I was prepared to make this sacrifice for the good of the oil analysis community, and plus, Blackstone was buying, so it really didn’t bother me too much. If you think about it, how lucky can you get to be able to buy little time capsules of a product and test it? Can you by beer from 30 years ago and still drink it? I guess, but chances are it’s long gone bad. How about a 30-year-old can of sardines, or a 5-year-old one for that matter? No way. So, I would really be a fool not to try this and see what shows up.

One thing led to another and before I knew it I had bought 28 cans of old oil and spent almost $1,000. Pretty soon these oils started rolling in and I experienced a little buyers remorse. Did I really need to buy all this? What was I going to do with the cans? Once you open a can of oil, it’s almost impossible to seal up properly. Would there be anything to even see in these samples? And, does oil go bad? We get this last question all the time, and my answer has always been no, but I was dealing with oils from the 1930s,1940s, and 1950s here–really old stuff. Maybe all the additive in there (if any was even used) would settle out and there wouldn’t be anything for us to read. Fortunately, I had bought some oil that would help answer that.

One thing led to another and before I knew it I had bought 28 cans of old oil and spent almost $1,000. Pretty soon these oils started rolling in and I experienced a little buyers remorse. Did I really need to buy all this? What was I going to do with the cans? Once you open a can of oil, it’s almost impossible to seal up properly. Would there be anything to even see in these samples? And, does oil go bad? We get this last question all the time, and my answer has always been no, but I was dealing with oils from the 1930s,1940s, and 1950s here–really old stuff. Maybe all the additive in there (if any was even used) would settle out and there wouldn’t be anything for us to read. Fortunately, I had bought some oil that would help answer that.

Shaken, not stirred

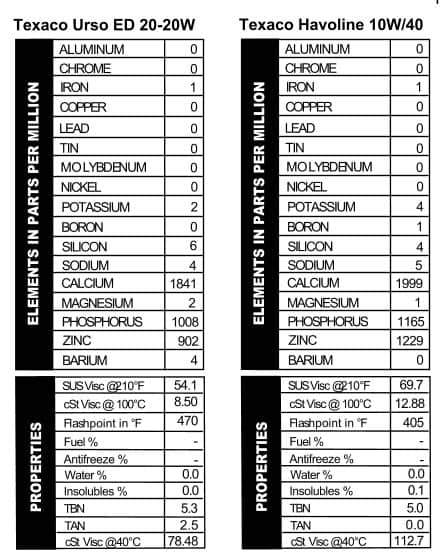

Before I did any testing, I wanted to see if I would need to shake these oils up. If the additive had fallen out of suspension, then all of these old cans would need to be shaken before I even opened them. Ideally, it would be great to have two oils of the same batch, so I could run one unshaken and run one shaken and see what type of difference shows up. That’s where my two antique vintage Havoline Texaco all-metal cans came into play. “SAE 20-20W” is stamped on the top of the can, and the text on the back says, “For API engine service classifications MM, MS, DG, and DM.” It also assured me that it’s “The finest engine protection in the world.”

I bought these two for $25.00 total, and going by what looks like a date on the can, I think they were from 1968. They were from the same seller and looked exactly the same. Chances are good they came from the same case someone bought years ago and they have been sitting on the shelf even since.

I decided to run a test. I would take one to the local hardware store (www.doitbest.com) and have them put it in the paint shaker for five minutes. Then I would crack them both open, test them, and see what differences showed up. You can see the results in Hav No Shake and Hav Shake.

To my surprise, there was actually more of some additive in the oil that I didn’t have shaken. Also, the additives really weren’t that different from what we see in today’s oil. The oil was supposed to be a straight 20W and it was. Also, it had a strong TBN, so the additive that was present was still active.

About the only unusual thing was that phosphorus was higher than zinc. Those two elements are normally from the ZDDP additive, but maybe there were using a different formula back in 1968. It’s hard to say, but from that test I learned that when it’s done right, the additives actually become part of the oil during blending and time/gravity alone won’t cause them to separate back out.

So that settled it. I didn’t need to shake all of these oils and could just start running them. That’s good because some of these old cans were bound to break open during shaking and spray oil all over Norm and his paint department.

But is it still good?

However, that really didn’t get down to answering the question: Is this oil still good to use? For that, I was going to have to run another test.

However, that really didn’t get down to answering the question: Is this oil still good to use? For that, I was going to have to run another test.

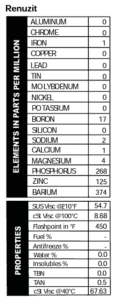

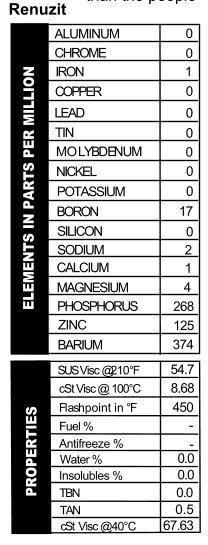

Of all the oils I bought, one of the most expensive was very rare—according to the seller, antique Renuzit Certified, Premium Quality 2500 Mile oil. Not only does this oil offer the ability to run the oil 2500 miles in between oil changes (“Cut your oil bills in half!”), but it claims to provide a longer engine life, smoother motor, stronger oil film, and best of all, “a faster getaway.” They don’t actually advertise it as the best oil for bank robbers, but they should have.

It cost $75.00 + $25.00 shipping, but I got a whole gallon of it. Unfortunately, the can had some rust on the bottom of it and it started leaking during shipping. The good news was, I now needed to do something with this oil and I wasn’t going to dump it in a waste barrel. So I am going to actually run this in my engine. Not in my Mini (it’s still under warranty), but my trusty old GM 350, rebuilt twice by yours truly.

I know what you are thinking—this SOB is out of his mind!—but don’t try to talk me out of it. I’m going to run this oil and decide once and for all if running old oil really hurts anything. Will my engine blow-by and leave me stranded on the side of the road? Will the seals start leaking like mad a leave a slick of oil behind for other cars to slip on and spin off into the ditch (a la Spy Hunter)? Will this be the end of my beloved 1984 Chevy Custom Deluxe? Well, like the monkey said after he shit in the corner—that remains to be seen!*

Castrol with Tungsten

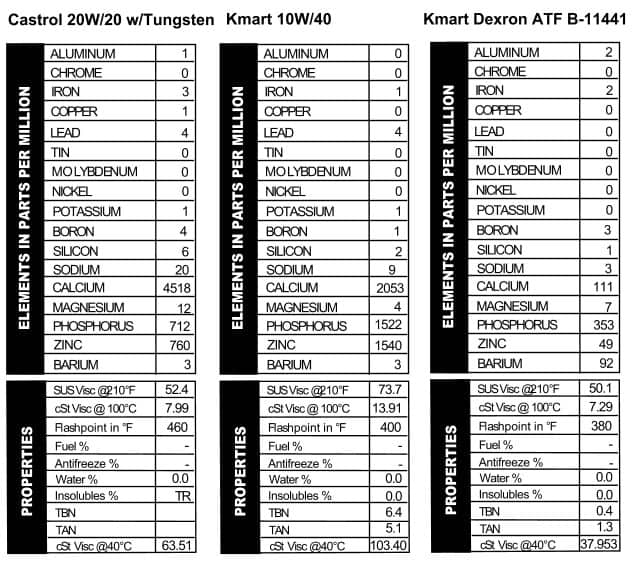

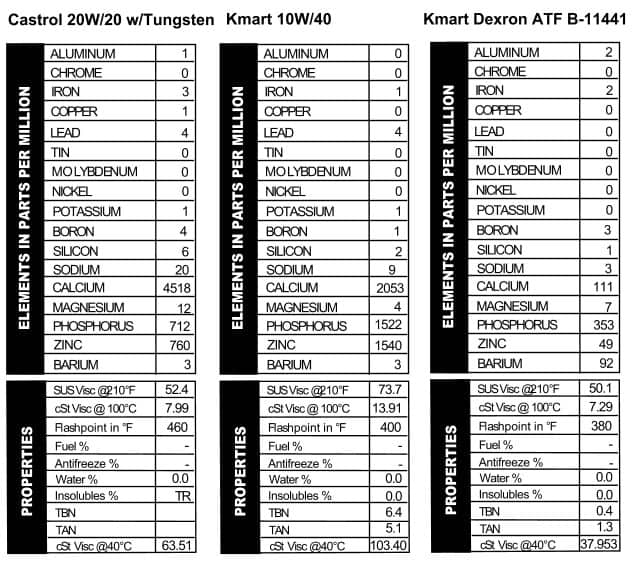

My first purchase was Castrol with Tungsten. Tungsten! What the hell? Since when did they start putting light bulb filaments in oil? Or maybe a better question would be, “When did they stop?” The bottle was partly in French, so I’m guessing it was from Canada, and that makes sense; the oil blenders up there will put anything in the oil and if the engine breaks, they just blame it on the cold. (Just kidding, Canadians! You know we love you guys.) I had to buy the single element standard to run Tungsten and set our spectrometer to run it, but after a little messing around, we got some results  .

.

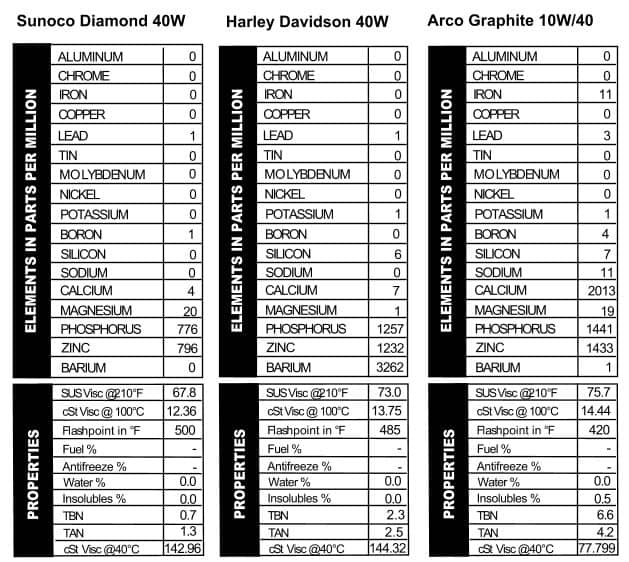

Sunoco DX Diamond motor oil – API SB

After seeing Castrol with Tungsten, I was ready for anything, but when I saw Sunoco’s Diamond oil, I didn’t really think they put diamonds in there. That would be one expensive additive. I did want to see what was in this SAE 40W oil though.

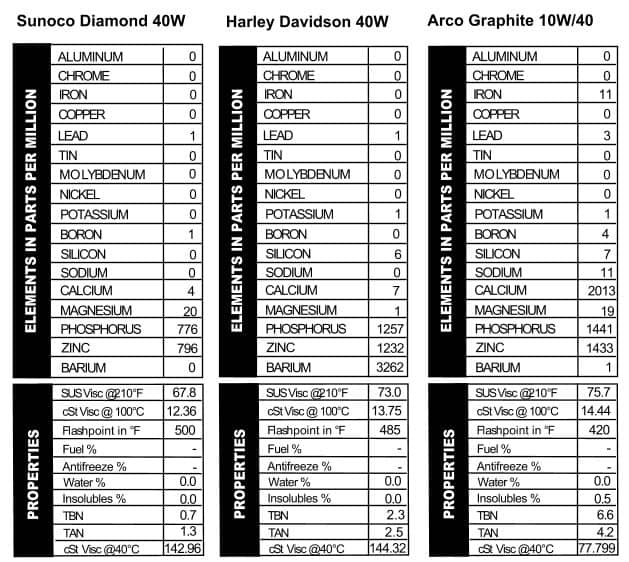

The case says is has an API rating of SB, which was used from 1930 to 1963. Several websites state that this oil can cause equipment harm. All I can say to that is, too bad I don’t have five quarts of this stuff, because I love a challenge. It doesn’t look so harmful in the oil analysis. The viscosity wasn’t quite in the 40W range and it didn’t have much in the way of detergent/dispersant additive present, but then again, it does state on the can that it is “Recommended for vehicles that do not require detergent oil.” Sometimes those oils don’t have any additive at all, but there was quite a bit of phosphorus and zinc here (figure 4).

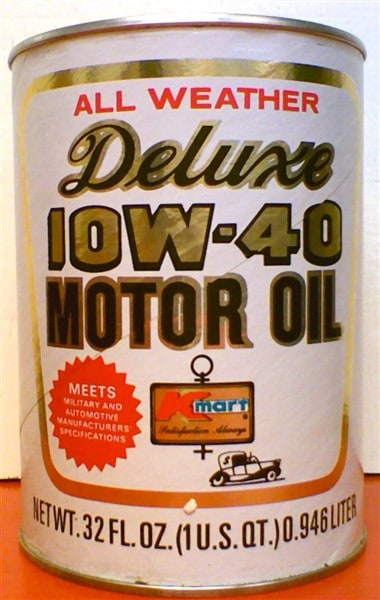

K-Mart 10W/40 Motor Oil (API SE) & DEXRON ATF

Back before Wal-Mart dominated the world, there was K-mart, and when I was in 4th grade, there was no greater crack on someone than “You buy your underwear at K-Mart.”

Well, I wonder what those boys would say if they found out I bought my oil at K-Mart too. The motor oil is listed as Deluxe and it says on the side of the can that this is specially blended multi-viscosity oil containing the finest approved additives and base oils. So you can’t go wrong there, right?

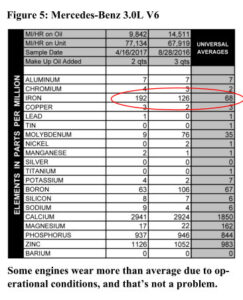

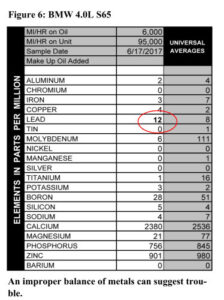

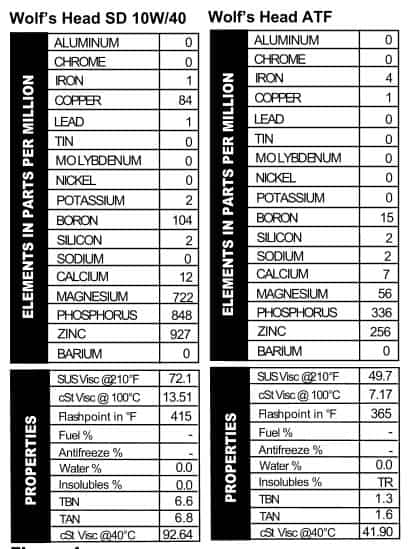

Looking at the results, I’d say this oil is indeed deluxe. The viscosity is pretty strong for a 10W/40, and the additives would be suitable for diesel use. The oil does have a CC rating as well as an SE rating, and those put the date of this oil as being made sometime in the 1970s. The ATF has a standard additive package until you get down to barium. That’s not used much anymore. See figures 5 and 6 for the analyses.

Looking at the results, I’d say this oil is indeed deluxe. The viscosity is pretty strong for a 10W/40, and the additives would be suitable for diesel use. The oil does have a CC rating as well as an SE rating, and those put the date of this oil as being made sometime in the 1970s. The ATF has a standard additive package until you get down to barium. That’s not used much anymore. See figures 5 and 6 for the analyses.

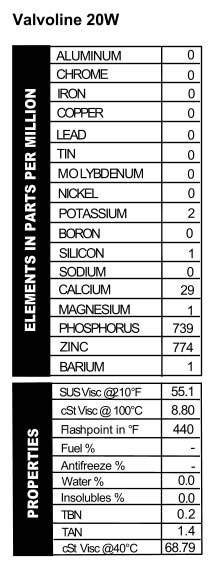

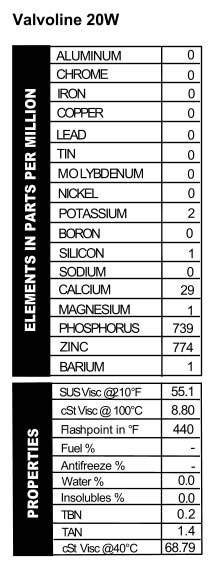

Valvoline SAE 20W – API SB

Valvoline SAE 20W – API SB

The big marketing claim for this oil says it “Contains Miracle ChemAloy.” Miracle! Really! Does the Pope know about this? There were no miracles in the additive package that I can see, but maybe that’s the miracle of it—you can’t see it, but it’s in there and it works. This oil doesn’t have much of a TBN because it doesn’t contain much calcium, but the old stand-bys of phosphorus and zinc are there, and at pretty much the same levels we see today (figure 7).

Harley-Davidson Premium Grade Motorcycle Oil (SAE 40) 75-P

This can caught my eye because it reminded me of Evel Knievel. In fact, the logo on the can is the same as what is on Evel’s website, so the two were heavily linked back in 1970s.

What’s interesting is that Harley-Davidson actually came up with their own oil weight specifications. This can is 75 Medium Heavy and is for use in all motors at temperatures above 40°F. They also made 58 Special Light, which is good for temperatures below 40°F, and 105 Regular Heavy—good for all motors operating under severe conditions at high (?) temperatures. Apparently, it was up to us to decide what high temperatures are; also, neither the 75 or 105 was “special.” I’m sure the special label added some extra cost and that made it special to Harley-Davidson.

Looking at the report, you’ll see this was a 40W oil and WOW look at the barium. That isn’t used much anymore and was likely some sort of detergent additive (figure 8).

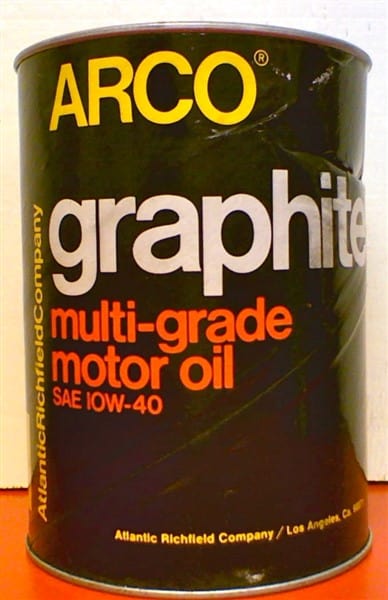

ARCO Graphite SAE 10W/40 (API SE-CC)

After seeing the word graphite in the name, I had to check this stuff out. True to its label, there was a lot of graphite in the oil (figure 9), and if you’re the kind of person who likes clean oil on your dipstick, this wasn’t the brand for you. Graphite is known as a lubricant, but I wonder how this stuff did in engines. Looking at the report, you can see the graphite at the insoluble reading of 0.5%. That’s extremely high for virgin oil, so the stuff doesn’t stay in suspension very well. On the plus side, the can says this oil provides

- Improved gasoline mileage

- Reduced piston ring and cam wear

- Easy low temperature starting and excellent lubrication at low and high operating temperatures

The oil is also “Patent Pending” and I’m wondering how that application is progressing down at the Patent office these days.

In Parts 2 and 3 of “The eBay Oils” we’ll be looking at old cans of Amsoil, Mobil, Valvoline, and more. Look for the next installments this summer!

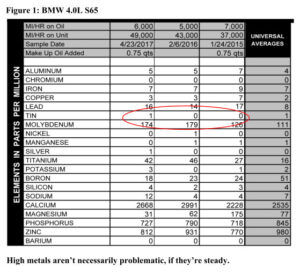

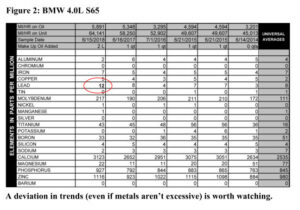

If you have them, trends are the most helpful thing we look at in determining your engine’s health. It takes three samples to get a good trend going (though we can often tell if something is amiss earlier than that).

If you have them, trends are the most helpful thing we look at in determining your engine’s health. It takes three samples to get a good trend going (though we can often tell if something is amiss earlier than that).

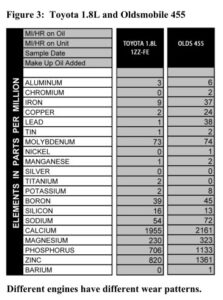

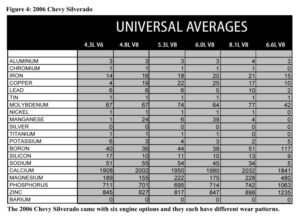

If we don’t know what kind of engine you have, we might end up comparing your numbers to the wrong set of averages, or just a generic engine file. We can still tell if something is way out of line, but the more subtle differences between your engine and averages are harder to see.

If we don’t know what kind of engine you have, we might end up comparing your numbers to the wrong set of averages, or just a generic engine file. We can still tell if something is way out of line, but the more subtle differences between your engine and averages are harder to see.

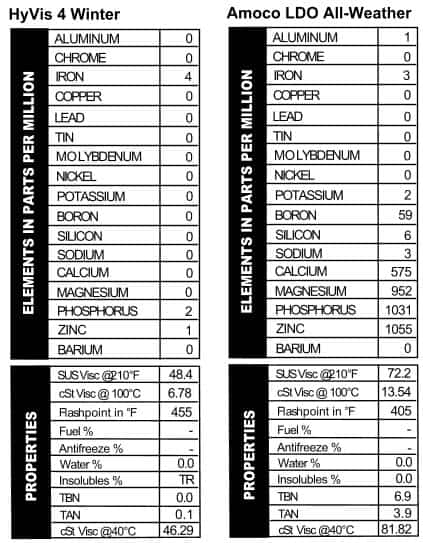

HyVis 4 Winter

HyVis 4 Winter additive in it, just not any that we read. The grade is not listed on the can, but the viscosity came back as a light 20W. With the lack of additive it’s not surprising that the TBN read 0.0. It’s tempting to do an experiment and run this apparent mineral oil for 10,000 miles in the dead of winter, just to see what would happen. If you know of any guinea pigs, send them our way!

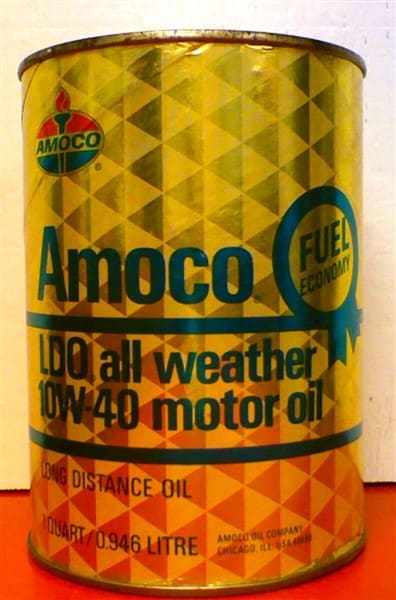

additive in it, just not any that we read. The grade is not listed on the can, but the viscosity came back as a light 20W. With the lack of additive it’s not surprising that the TBN read 0.0. It’s tempting to do an experiment and run this apparent mineral oil for 10,000 miles in the dead of winter, just to see what would happen. If you know of any guinea pigs, send them our way! the country, and I’ll always associate the blue, red, and white logo with long trips across the country in our green van with the velour bed and hanging beads. But Amoco did more than fill up gas tanks in the 70s–they also sold oil, and this “Long Distance” version is an SAE 10W/40. The additive package looks a lot like the Mobil Special oil we saw: heavy on phosphorus and zinc, lighter on calcium and magnesium (Figure 2). Just the right oil for a couple of bandana-wearing hippies traveling with two little kids from Indiana to Nova Scotia in 1976 in a green van with a sunset painted on the side. Ah, the ’70s.

the country, and I’ll always associate the blue, red, and white logo with long trips across the country in our green van with the velour bed and hanging beads. But Amoco did more than fill up gas tanks in the 70s–they also sold oil, and this “Long Distance” version is an SAE 10W/40. The additive package looks a lot like the Mobil Special oil we saw: heavy on phosphorus and zinc, lighter on calcium and magnesium (Figure 2). Just the right oil for a couple of bandana-wearing hippies traveling with two little kids from Indiana to Nova Scotia in 1976 in a green van with a sunset painted on the side. Ah, the ’70s. The viscosity read like what we see today out of a standard 5W/30. Texaco Havoline Super Premium 10W/40, on the other hand, looks a lot like one of today’s diesel-use oils in additives (Figure 4), with a normal 10W/40 viscosity.

The viscosity read like what we see today out of a standard 5W/30. Texaco Havoline Super Premium 10W/40, on the other hand, looks a lot like one of today’s diesel-use oils in additives (Figure 4), with a normal 10W/40 viscosity.

only did they not make multi-viscosity oils that long ago, but the can comes from zip code 90017 so it has to be from 1963 or later. According to the can, it’s 100% parrafinic oil with selected additives, which our spectrometer reveals to be your standard line-up of calcium, phosphorus, and zinc (Figure 6). Look at that viscosity though¾it’s higher than we see in today’s 20W/50s.

only did they not make multi-viscosity oils that long ago, but the can comes from zip code 90017 so it has to be from 1963 or later. According to the can, it’s 100% parrafinic oil with selected additives, which our spectrometer reveals to be your standard line-up of calcium, phosphorus, and zinc (Figure 6). Look at that viscosity though¾it’s higher than we see in today’s 20W/50s.

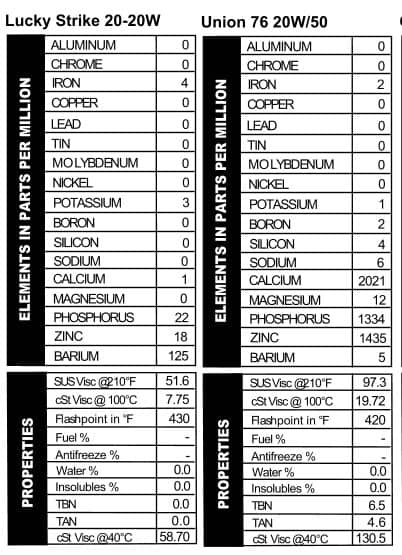

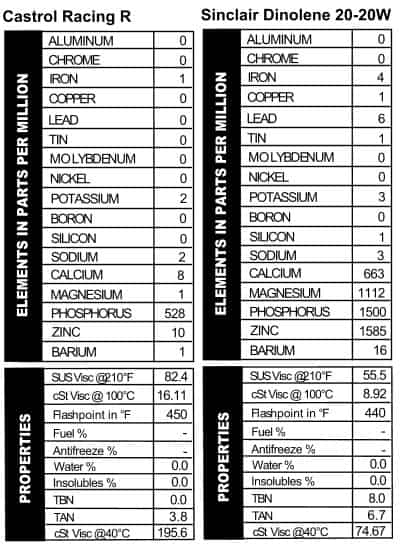

Like modern oils, they stress the high quality of the oil with terms like “organo-metallic” that are meant impress those of us who aren’t in the oil business. I don’t know if I’d call this a masterpiece in oil work though: it looks like what we see out of ATFs these days as far as additives go (mostly phosphorus with a little zinc thrown in). Since the word “Racing” is stamped into the top of the can, the thick viscosity (like a 50W) makes sense (Figure 7).

Like modern oils, they stress the high quality of the oil with terms like “organo-metallic” that are meant impress those of us who aren’t in the oil business. I don’t know if I’d call this a masterpiece in oil work though: it looks like what we see out of ATFs these days as far as additives go (mostly phosphorus with a little zinc thrown in). Since the word “Racing” is stamped into the top of the can, the thick viscosity (like a 50W) makes sense (Figure 7). I’ve always had a soft spot in my heart for Sinclair. The can has a picture of a dinosaur on it! This shit came from the ground, no doubt about it! Another 20-20W oil, the oil is light on advertising copy but heavy on additives. In fact, it looks a lot like recent versions of Shell’s Rotella 5W/40, except with a little less calcium. It’s much lighter than Shell’s 5W/40, though, with a viscosity reading like a 30W or a heavy 20W oil. Note the presence of lead (Figure 8).

I’ve always had a soft spot in my heart for Sinclair. The can has a picture of a dinosaur on it! This shit came from the ground, no doubt about it! Another 20-20W oil, the oil is light on advertising copy but heavy on additives. In fact, it looks a lot like recent versions of Shell’s Rotella 5W/40, except with a little less calcium. It’s much lighter than Shell’s 5W/40, though, with a viscosity reading like a 30W or a heavy 20W oil. Note the presence of lead (Figure 8).

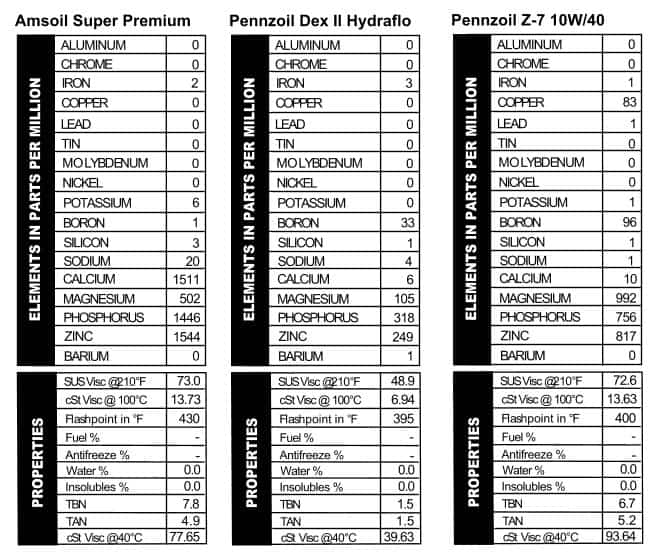

Modern Amsoil products tend to be heavy on additives and that was true back in the day as well (Figure 9). Just for fun, we compared this oil with a virgin sample of Amsoil 10W/40 that we ran in February 2012 and they look a lot alike. The only difference is in the older oil there’s less of everything: 500 ppm less calcium, and 100-200 ppm less phosphorus and zinc. They used magnesium in the older oil, while the TBN and viscosities were nearly identical.

Modern Amsoil products tend to be heavy on additives and that was true back in the day as well (Figure 9). Just for fun, we compared this oil with a virgin sample of Amsoil 10W/40 that we ran in February 2012 and they look a lot alike. The only difference is in the older oil there’s less of everything: 500 ppm less calcium, and 100-200 ppm less phosphorus and zinc. They used magnesium in the older oil, while the TBN and viscosities were nearly identical. over these two old cans. Originally, Penn’s Oil came from an oil field in Pennsylvania and was christened with a Liberty Bell logo to remind users of its Pennsylvania roots. This can of ATF clearly has an earlier generation of logo on it, and Google informs me that Dexron II was introduced in 1972. This may very well have been the transmission oil that kept our green van chugging through the ’70s. There are a lot of different ATFs in stores today, though generally they have about the same additive configurations. This one is a little different in that it has more boron, magnesium, and zinc than most modern ATFs. The viscosity is right where we’d expect it to be though. Pennzoil’s 10W/40 oil can is flashy, a la the

over these two old cans. Originally, Penn’s Oil came from an oil field in Pennsylvania and was christened with a Liberty Bell logo to remind users of its Pennsylvania roots. This can of ATF clearly has an earlier generation of logo on it, and Google informs me that Dexron II was introduced in 1972. This may very well have been the transmission oil that kept our green van chugging through the ’70s. There are a lot of different ATFs in stores today, though generally they have about the same additive configurations. This one is a little different in that it has more boron, magnesium, and zinc than most modern ATFs. The viscosity is right where we’d expect it to be though. Pennzoil’s 10W/40 oil can is flashy, a la the  1980s. It’s “The Motor Oil With Z-7” and although they don’t specify what that is, they do specify that “You need no extra oil additive.” So that’s reassuring. It’s rated SF-SC-CC, so I’d place it at about 25 years old. Maybe the magic of Z-7 is copper: that’s something we saw a lot of back in the day, when Blackstone was founded. Interestingly, magnesium is the dominant additive in this one, followed by zinc, phosphorus, copper, and boron (Figure 10). The flashpoint was lower than what we see today from 10W/40s.

1980s. It’s “The Motor Oil With Z-7” and although they don’t specify what that is, they do specify that “You need no extra oil additive.” So that’s reassuring. It’s rated SF-SC-CC, so I’d place it at about 25 years old. Maybe the magic of Z-7 is copper: that’s something we saw a lot of back in the day, when Blackstone was founded. Interestingly, magnesium is the dominant additive in this one, followed by zinc, phosphorus, copper, and boron (Figure 10). The flashpoint was lower than what we see today from 10W/40s.

a can like the others. This one was sold in a 5-quart metal jug. I particularly love this one, because the can not only says you’ll “Cut Your Oil Bills In Half,” but the first point of advertising on the side is a “Faster Getaway!” Now, they don’t actually say that this is the choice of oils for bank robbers, but I know if it was 1941 and my hungry Great Depression self was contemplating which oil to put in my Ford Special for bank-robbing time, this is the oil I’d pick. With practically no calcium or magnesium present, the oil’s TBN read 0.0, but it does provide would-be crooks with phosphorus, zinc, and barium as well as a 20W viscosity for the getaway (Figure 11). When you’re busy working a tommy gun, the last think you want to think about is whether or not you’ve made the right choice in oil.

a can like the others. This one was sold in a 5-quart metal jug. I particularly love this one, because the can not only says you’ll “Cut Your Oil Bills In Half,” but the first point of advertising on the side is a “Faster Getaway!” Now, they don’t actually say that this is the choice of oils for bank robbers, but I know if it was 1941 and my hungry Great Depression self was contemplating which oil to put in my Ford Special for bank-robbing time, this is the oil I’d pick. With practically no calcium or magnesium present, the oil’s TBN read 0.0, but it does provide would-be crooks with phosphorus, zinc, and barium as well as a 20W viscosity for the getaway (Figure 11). When you’re busy working a tommy gun, the last think you want to think about is whether or not you’ve made the right choice in oil.

Wolf’s Head SD 10W/40

Wolf’s Head SD 10W/40 Wolf’s Head ATF

Wolf’s Head ATF white, and blue, so you can feel patriotic when you buy it (unless

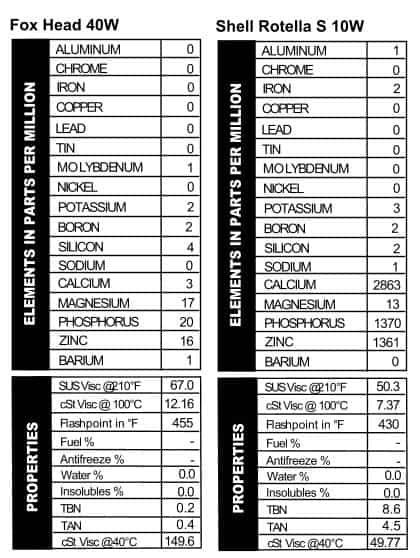

white, and blue, so you can feel patriotic when you buy it (unless  you’re in Canada. Then you can indulge in justified rage about Americans and how we think we’re the center of the world). Fox Head oil was made by the Tritex Petroleum company out of Brooklyn, NY, and my extensive research (aka first-page Google results) tells me the company still exists and is presently located in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The logo, a sly-looking fox, has nothing on today’s slick oil packages. And the oil itself also has nothing on today’s oils: the oil itself is nearly bereft of additives. Basically a mineral oil, it has a little magnesium, phosphorus, and zinc in it, and not a lot else (Figure 3). This is not necessarily a problem, however. As you’ll recall in the article when Ryan used 30W aircraft oil in his truck, wear went up a little but the engine didn’t fail or anything. Still, I won’t be putting it in my Outback anytime soon.

you’re in Canada. Then you can indulge in justified rage about Americans and how we think we’re the center of the world). Fox Head oil was made by the Tritex Petroleum company out of Brooklyn, NY, and my extensive research (aka first-page Google results) tells me the company still exists and is presently located in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The logo, a sly-looking fox, has nothing on today’s slick oil packages. And the oil itself also has nothing on today’s oils: the oil itself is nearly bereft of additives. Basically a mineral oil, it has a little magnesium, phosphorus, and zinc in it, and not a lot else (Figure 3). This is not necessarily a problem, however. As you’ll recall in the article when Ryan used 30W aircraft oil in his truck, wear went up a little but the engine didn’t fail or anything. Still, I won’t be putting it in my Outback anytime soon. long they’ve been making this oil and the guy not only could not tell me, but he was unable to tell me who might know. Surely someone at that company has a historical file? If so, they’re not sharing that info with plebeians like us. He did mention that Rotella really made its name in the ’70s, though I’m guessing this can of SF, SE, SC oil was made in the late ’80s. He also said the “S” versions of Rotella were sold internationally, and indeed, this can came from our friendly neighbors to the north (*waves hi to Canada). Suffice it to say that the oil has changed very little over the years. Its main additives are the same as what we see today, but the interesting part of this oil is that it’s a 10W (Figure 4). We often see heavy-duty thin-grade additive packages in tractor-hydraulic fluids, which are used in systems like transmissions and hydraulic systems in off-highway equipment like bulldozers and backhoes. Note the TBN of this oil read higher than most of the others we’re talking about. That’s because of the high calcium level¾the TBN is based on the level of calcium sulfinate and/or magnesium sulfinate. When those compounds aren’t present, you get a low TBN.

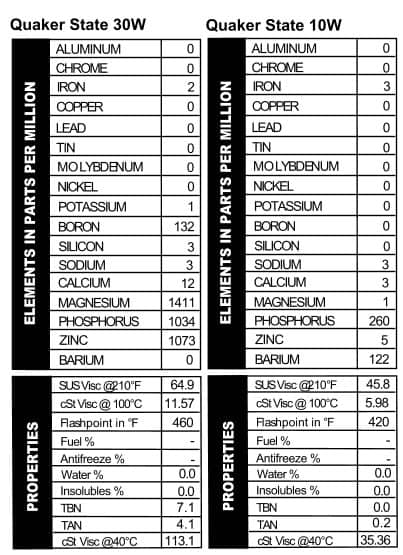

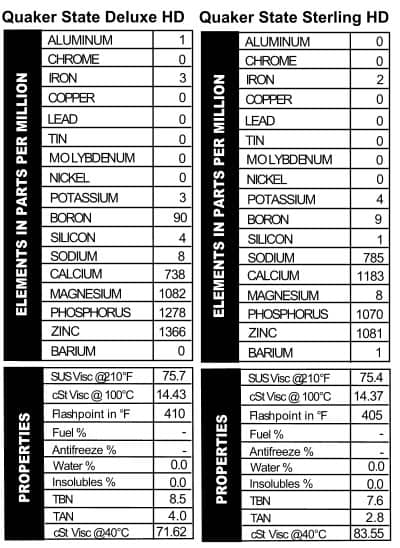

long they’ve been making this oil and the guy not only could not tell me, but he was unable to tell me who might know. Surely someone at that company has a historical file? If so, they’re not sharing that info with plebeians like us. He did mention that Rotella really made its name in the ’70s, though I’m guessing this can of SF, SE, SC oil was made in the late ’80s. He also said the “S” versions of Rotella were sold internationally, and indeed, this can came from our friendly neighbors to the north (*waves hi to Canada). Suffice it to say that the oil has changed very little over the years. Its main additives are the same as what we see today, but the interesting part of this oil is that it’s a 10W (Figure 4). We often see heavy-duty thin-grade additive packages in tractor-hydraulic fluids, which are used in systems like transmissions and hydraulic systems in off-highway equipment like bulldozers and backhoes. Note the TBN of this oil read higher than most of the others we’re talking about. That’s because of the high calcium level¾the TBN is based on the level of calcium sulfinate and/or magnesium sulfinate. When those compounds aren’t present, you get a low TBN. Quaker State 30W & 10W

Quaker State 30W & 10W

these oils are mostly the same; they’ll throw in a few slight differences in additives and call it good. These cans of Quaker State, however, were mostly pretty different. The Deluxe version looked a lot like their 30W oil (but more calcium–Figure 7). Quaker State Sterling HD 10W/40, on the other hand, went out on a limb with almost 800 ppm sodium, almost no magnesium, and then levels of calcium, phosphorus, and zinc that are comparable with today’s oils. Touted as “Energy Saving Motor Oil,” Quaker State was getting its game on in pushing this brand: it mentions “special friction modifying additives,” the longevity of the company (over 60 years when the can was made), and its suitability for those wishing to follow extended drain intervals. Heck, I’m sold, and I see this stuff all the time.

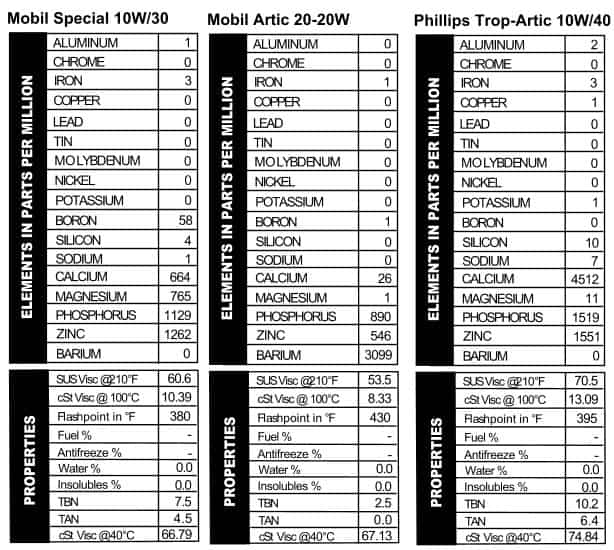

these oils are mostly the same; they’ll throw in a few slight differences in additives and call it good. These cans of Quaker State, however, were mostly pretty different. The Deluxe version looked a lot like their 30W oil (but more calcium–Figure 7). Quaker State Sterling HD 10W/40, on the other hand, went out on a limb with almost 800 ppm sodium, almost no magnesium, and then levels of calcium, phosphorus, and zinc that are comparable with today’s oils. Touted as “Energy Saving Motor Oil,” Quaker State was getting its game on in pushing this brand: it mentions “special friction modifying additives,” the longevity of the company (over 60 years when the can was made), and its suitability for those wishing to follow extended drain intervals. Heck, I’m sold, and I see this stuff all the time. Mobil is no slouch in the marketing department, but they really outdid themselves with the can we tested, “Mobil Special.” The name alone tells you all you need to know about why to buy this oil. All oil companies like to mess with their additive packages, and Mobil, like the others, changes their oil up fairly frequently. That was the case back in the day too, because the additive package in this “Special” oil is different from what we typically see in today’s oil. Apparently Mobil was an early rider on the ZDDP train, because this oil is chock-full of both phosphorus and zinc. Calcium and magnesium are present too, but at lower levels (Figure 8). We also tested a sample of Mobil Artic oil. The Artic

Mobil is no slouch in the marketing department, but they really outdid themselves with the can we tested, “Mobil Special.” The name alone tells you all you need to know about why to buy this oil. All oil companies like to mess with their additive packages, and Mobil, like the others, changes their oil up fairly frequently. That was the case back in the day too, because the additive package in this “Special” oil is different from what we typically see in today’s oil. Apparently Mobil was an early rider on the ZDDP train, because this oil is chock-full of both phosphorus and zinc. Calcium and magnesium are present too, but at lower levels (Figure 8). We also tested a sample of Mobil Artic oil. The Artic can is clearly older than the other Mobil can¾the logo is older, and there’s no zip code listed with the address, so it’s pre-1963. A straight 20W, it’s labeled as HD oil, meeting “Car Builders’ Most Severe Service Tests.” While it’s “Artic” and not “Arctic,” we can’t help thinking this oil is meant for cold-weather operation. The can even looks like it’s ready for winter: all white, but with a little color on it so you don’t lose it in the snow when you’re out in the tundra changing your oil. This one definitely has an unusual additive package, relying heavily on barium (maybe it’s got a purpose after all!). Interestingly, less zinc is present than phosphorus (Figure 9). Nowadays it’s the other way around.

can is clearly older than the other Mobil can¾the logo is older, and there’s no zip code listed with the address, so it’s pre-1963. A straight 20W, it’s labeled as HD oil, meeting “Car Builders’ Most Severe Service Tests.” While it’s “Artic” and not “Arctic,” we can’t help thinking this oil is meant for cold-weather operation. The can even looks like it’s ready for winter: all white, but with a little color on it so you don’t lose it in the snow when you’re out in the tundra changing your oil. This one definitely has an unusual additive package, relying heavily on barium (maybe it’s got a purpose after all!). Interestingly, less zinc is present than phosphorus (Figure 9). Nowadays it’s the other way around. see out of modern 15W/40s¾a stout additive package and a relatively thick viscosity (Figure 10). In other words, even though this oil is several decades old, it would be fine to use in your F150 tomorrow.

see out of modern 15W/40s¾a stout additive package and a relatively thick viscosity (Figure 10). In other words, even though this oil is several decades old, it would be fine to use in your F150 tomorrow.

and needed some oil for my Passat. It just starting to clatter a little on start up and when I checked the oil, it was down two quarts. The clatter sounded something like “Sell Me” in German.

and needed some oil for my Passat. It just starting to clatter a little on start up and when I checked the oil, it was down two quarts. The clatter sounded something like “Sell Me” in German.

One thing led to another and before I knew it I had bought 28 cans of old oil and spent almost $1,000. Pretty soon these oils started rolling in and I experienced a little buyers remorse. Did I really need to buy all this? What was I going to do with the cans? Once you open a can of oil, it’s almost impossible to seal up properly. Would there be anything to even see in these samples? And, does oil go bad? We get this last question all the time, and my answer has always been no, but I was dealing with oils from the 1930s,1940s, and 1950s here–really old stuff. Maybe all the additive in there (if any was even used) would settle out and there wouldn’t be anything for us to read. Fortunately, I had bought some oil that would help answer that.

One thing led to another and before I knew it I had bought 28 cans of old oil and spent almost $1,000. Pretty soon these oils started rolling in and I experienced a little buyers remorse. Did I really need to buy all this? What was I going to do with the cans? Once you open a can of oil, it’s almost impossible to seal up properly. Would there be anything to even see in these samples? And, does oil go bad? We get this last question all the time, and my answer has always been no, but I was dealing with oils from the 1930s,1940s, and 1950s here–really old stuff. Maybe all the additive in there (if any was even used) would settle out and there wouldn’t be anything for us to read. Fortunately, I had bought some oil that would help answer that.

However, that really didn’t get down to answering the question: Is this oil still good to use? For that, I was going to have to run another test.

However, that really didn’t get down to answering the question: Is this oil still good to use? For that, I was going to have to run another test. .

. Looking at the results, I’d say this oil is indeed deluxe. The viscosity is pretty strong for a 10W/40, and the additives would be suitable for diesel use. The oil does have a CC rating as well as an SE rating, and those put the date of this oil as being made sometime in the 1970s. The ATF has a standard additive package until you get down to barium. That’s not used much anymore. See figures 5 and 6 for the analyses.

Looking at the results, I’d say this oil is indeed deluxe. The viscosity is pretty strong for a 10W/40, and the additives would be suitable for diesel use. The oil does have a CC rating as well as an SE rating, and those put the date of this oil as being made sometime in the 1970s. The ATF has a standard additive package until you get down to barium. That’s not used much anymore. See figures 5 and 6 for the analyses. Valvoline SAE 20W – API SB

Valvoline SAE 20W – API SB