What’s the Best Oil Change Interval?

Here’s an interesting question we received recently from Pete, one of our long-time customers:

“Needed to ask you about AMSoil OE synthetic oil. The change interval that is suggested for that oil is whatever the vehicle manufacturer has specified for that particular vehicle. But what have you seen from the TBNs that you have run on that oil? It doesn’t make sense that in my old 01 Maxima it would only be good 3000 miles but in a brand new vehicle it could be good for 10K.”

Pete has a point. Why would the same oil wear out faster just because the manufacturer recommends a shorter oil change interval? If the oil can hold up for 10,000 miles or more in some engines, shouldn’t it be able to do so in any type of engine?

Of course, there are some reasonable explanations that Amsoil (or any oil manufacturer) might give for this. The industry is generally moving towards longer oil change recommendations because modern engines are built to more exacting standards than they were even ten years ago, allowing for improved efficiency and less damage to the oil.

Plus, you might have to adjust the oil change interval in the same exact engine based on whether you’re seeing “severe” duty or not, so it’s probably reasonable to think that some types of engines would just treat the oil a little more harshly, and require a shorter oil run, right?

The cynical side of me, though, says that the real answer to this question probably has more to do with the legal department than the oil’s engineers. Regardless of how good you think your oil is, if you start telling customers they can ignore the original engine manufacturer’s recommendations, you’re probably opening yourself up to some legal headaches that the head office just doesn’t want to deal with.

But true as that may be, it’s not a very good answer for Pete, or the rest of our customers who are just looking for the best advice on how to treat their vehicles. So setting aside specific recommendations for a moment, let’s get to the nut of Pete’s question… Does the life expectancy of the oil change based on what engine it’s used in?

The tale of the TBN

There are several factors that we use to determine if your oil can be run longer, but Pete asked specifically about the TBN, so let’s focus on that for now.

For those who don’t know, the TBN (Total Base Number) measures the amount of active additive remaining in the oil. A typical gasoline-engine oil might have a starting TBN between 6.0 and 8.0, while diesel-use engine oils tend to have higher TBN’s of 11.0 or 12.0, since they have to deal with dirtier, more acidic conditions.

But regardless of where a TBN starts, they all end up in the same place—0.0—if the oil is run too long. Once the TBN is down to zero, it means that the oil is no longer able to neutralize acids produced by the engine. As a general rule of thumb, we usually say that once a TBN gets lower than about 2.0, it would probably be a good idea not to run the oil much longer, to avoid running out of those active acid-neutralizing agents.

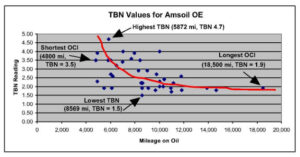

To answer Pete’s question about how the TBN of Amsoil OE holds up in different engines, we searched our database to find the recent TBN results we’ve seen from that type of oil. Since the TBN is an optional test, we don’t run it on every sample we see, but customers who use Amsoil tend to be pretty interested in seeing how long they can run their oil, so we have a pretty good representation for that oil type. We plotted nearly 50 samples’ TBN results against the mileage on the oil, and came up with this graph:

The banana-shaped line we’ve drawn approximates the “average” TBN for this type of oil over a given mileage. You can see that the TBN tends to drop quickly at first, but the longer the oil is run, the slower the TBN drops. Of the samples we tested, none of them had a TBN less than 1.5, so even on very long oil change intervals, this Amsoil OE oil tends to retain plenty of active additive.

Also note that the actual test results (the dots) can stray pretty far from that line on either side, so even though the TBN readings tend to follow a particular pattern, there can be a pretty wide deviation in individual test results. Just at a glance, you can easily see that the sample with the highest TBN reading didn’t have the lowest mileage on the oil, nor did the sample with the longest oil run (a whopping 18,500 miles) have the lowest TBN reading. In fact, the lowest TBN came after a fairly middle-of-the-road 8,569-mile oil change interval.

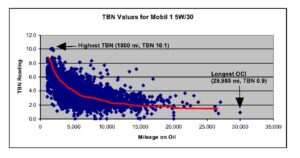

And before we get too hung up on looking at just Amsoil OE, we ran the same analysis for one of the most common oil types we’ve tested, Mobil 1 5W/30, resulting in the following chart:

The graph for Mobil 1 5W/30 covers nearly 5,000 samples with TBNs, and the scale is a little different than the Amsoil OE chart, but you can see that banana-shaped curve that we’ve drawn, approximating the average TBN for a given mileage, is exactly the same as in the Amsoil OE chart. Once again, the highest TBN was not the shortest oil run, and the lowest TBN was not the longest oil run. So even though we have many more TBN data points for Mobil 1 as we do Amsoil OE, the overall trends for TBNs are similar, and would be with just about any type of oil you could name.

What affects the TBN?

So what other factors might be affecting the TBN? To find out, we ranked all the samples according to both mileage and TBN reading, and came up with the best and the worst of the bunch.

One factor that definitely stood out was make-up oil. If you add some fresh oil in between oil changes to top up your oil level, you’re infusing the oil with more active additives, and diluting wear metals and contaminants at the same time. That’s why we often say that you shouldn’t be too upset about adding a quart or two of oil over the course of your regular oil interval (assuming you don’t have a noticeable leak, of course), since that fresh oil might buy you a few thousand extra miles before you have to do a full oil change.

In this case, all of the samples that noted adding a quart of oil or more ranked in the top half of the results, and the Amsoil samples with the most oil added (2.5 and 3 quarts) ranked at numbers 2 and 7, respectively. On the other hand, the overall best-ranked sample, with a TBN of 4.0 after 10,000 miles, didn’t add any oil in that time, according to their oil slip, so make-up oil alone is not the only relevant factor.

Pete’s original question was about manufacturer’s recommended oil change intervals. We don’t have a list of the recommended OCI for every engine we’ve tested, so we’ll have to settle for looking at some other factors, like the age and size of the engine.

For both the Amsoil and the Mobil 1 samples, the age of the engine didn’t seem to make much of a difference. We had engines from the late 90’s and early 2000’s in the top ten percent on both charts, mixed right in with new engines from the last few model years. The total engine mileage was also mixed, with higher-mileage engines ranked right alongside brand new engines in their first few oil changes.

Engine size is one factor that I thought would end up playing a pretty big role, but I wasn’t sure which way it would go. On the one hand, larger engines tend to work harder, so I wondered if the larger 6-cylinder engines and big V8s might burn through the active additive more quickly than smaller engines. On the other hand, 4-cylinder engines also tend to have smaller oil sumps, meaning less total oil volume in the engine, so maybe their active additives get used up sooner.

Mixed results

Turns out there results were pretty mixed as well… there was a bit of a trend for smaller engines to hold a higher TBN for longer oil runs, but there were plenty of larger engines near the top ranks of both lists, and vice versa. Seems like the extra oil in the sump of the larger engines pretty much balances out the extra work they have to do, resulting in a mostly even distribution of engine sizes across the rankings in both charts.

So what does all this tell us? Well, at least as far as the TBNs go, it doesn’t look like the type of engine has much of an influence on how long the active additive lasts in the oil. Engines of the exact same type (and in some cases, even the exact same engines) were ranked both high and low in our results, so it looks like individual driving habits and the behavior of each particular engine play a much larger role than engine sizes, model years, manufacturers, or any other criteria we could see.

When you get right down to it, though, the TBN is only one factor in determining whether or not it’s safe to run the oil longer. It’s a valuable tool, but we also have to look at other factors, like wear metals, insolubles, viscosity, and contaminants, any of which could indicate that you shouldn’t run the oil any longer, even if the TBN is still good.

The bottom line is this: the lawyers have to tell you to follow the engine manufacturer’s recommendations, since they have no idea what’s going on with your particular vehicle. And really, the original engine manufacturer doesn’t have much better of an idea—they know how their engines should wear, and base their recommendations on what should work best for most drivers, but they don’t have any idea about your particular driving habits or maintenance routines.

When you get your oil analyzed at Blackstone, we’re looking at the specific conditions for your specific engine, which is why we can tell you if it’s safe to add an extra 2,000 or 3,000 miles on your next fill, regardless of your current OCI. Just check “Yes” next to the question “Are you interested in extended oil use?” on the back of your next oil slip, and maybe you too will be free to explore the world of extended oil use!