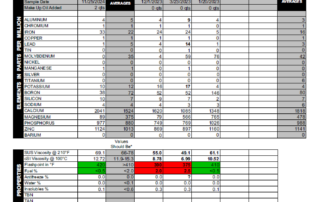

Viscosity: Going Down!

April of 2017 will mark my 20th year here at Blackstone and in that time a lot of changes have taken place. I’m a big fan of change myself and long ago got some advice from my Uncle Dan who said, “The only thing that’s constant in life is change.” I decided that his words were the truth, and it seems to me like change should be embraced because there is no stopping it, and also for the most part change is good. It might not seem good on the outset, but if you give it some time, things eventually work out. After a bit of reflection on the changes in the oil industry, I’ve decided that one of the best ones has been the trend to lower viscosity oils.

The thin oil trend

I started changing my own oil on a regular basis in the early ’90s, and at that time 10W/30 was the oil of choice in my 1981 Chevy Citation. I didn’t think that much about it. It said right on the oil cap use 10W/30, so I bought whatever was on sale and went along fat, dumb, and happy.

At that time 5W/30 oil was starting to be as common as 10W/30 on the shelves, but I never went with it because it wasn’t what GM said to use. However, my wife’s first car (1994 Buick Skylark) recommended 5W/30, so that was a sign that thinner oils were starting to come into favor. Again, I didn’t think much about it, and basically just stuck with what was recommended when I changed her oil.

Then, in the early 2000s I noticed that we were starting to see a lot of samples from Ford V-8 engines that were running 5W/20 oil. This was a bit of a surprise since that’s pretty thin oil, but it was hard to argue with the results. Those engines produced some of the best wear we would see on a regular basis, so it quickly because obvious to me that this was a change for the better. And if you think about it, it makes sense.

Wear at start-up

For years, it was taken as fact by a lot of people that most of the wear in an engine happens at start-up. Now I haven’t done any studies myself to see if that was true, but that statement didn’t seem out of line from what I know about engines.

So assuming it’s true, why would just starting an engine cause wear? Well, I believe the answer is the oil isn’t flowing over all of the parts like it does shortly after start-up. I do know that engines have virtually no metals parts touching one another without a thin film of oil providing a lubrication barrier, at least once oil pressure has been established. I also know that thin oil pumps easier than thick oil, so it’s seems obvious that the quicker you can get the oil to the parts, the less wear an engine will produce. From then on I was sold on thin oil.

So what’s the problem here? Well, when I first started at Blackstone, I was told that thick oil is good for the bearings, and I didn’t have cause to doubt that statement until I saw these Ford V-8s producing virtually no wear, and I knew some of them were work trucks that were hauling heavy loads. So could it be that the bearings didn’t need thin oil to survive? The answer is a resounding yes.

Even for diesels?

That trend toward thinner oil has proven true everywhere except for diesel engines. For years and years and even today, the oil of choice in a diesel was/is 15W/40. But, if a heavy-duty gas engine can run light oil, why can’t a diesel?

We would occasionally see diesel samples from Alaska that were running 5W/30 and they would look fine, so why not use it down here in the lower 48? In colder weather, it was acceptable for diesel to run thin oil, but that really only matters on start-up. But the oil doesn’t get thicker as it heats up¾it thins out.

So could it be that thin oil does fine even when it get gets up to operating temperature? The answer to me was another resounding yes, and I wondered when the day would come that 15W/40 would not longer be the manufacturer’s choice foe diesel engines. Well, that change has come!

Today we are starting to see more diesel fleets going to 10W/30, and I’m here to tell you that this change is good. Not only will the bearings do just fine, but the engines will start up better (especially in the cold). Now, there will always be some people who are resistant to change. In fact that are whole countries that are. The German vehicle manufacturers have yet to embrace thin oil, though I think that change will happen someday.

Yes, change is good and I have yet to see a change happen that leaves hundreds of thousands vehicles stuck along the side of the road. The sulfur has been virtually removed from diesel fuel and your old tractor still runs fine* (if this statement makes you mad, see my note below). Additive levels have been lowered in engine oil and the old flat-tappet engines still run great. And now thinner oils are here to stay. I’m excited to see what the changes the next 20 years might bring and I believe that I’ll embrace it, unless it involves getting rid of oil altogether!

*Note: Don’t get mad at me. I wasn’t in charge of that change and your injectors/fuel pump were probably on their way out anyway!

Fuel in Diesels

For our last newsletter, we did an experiment where we actually tried to get fuel dilution to show up in the oil. Amanda’s Kia was our guinea pig, and she tried hard to get some fuel to show up but had very little success. She tried idling for ten minutes and she tried lots of city driving, but could hardly get anything more than a trace or so. Maybe that’s just a testament to Kia and their fuel system engineering, or maybe she was just unlucky. It’s hard to say. However, fuel dilution does show up for a lot of our customers and after the last newsletter, we received some e-mails asking for more information about fuel, especially in diesel engines with possible fuel dilution problems.

A little history

Diesel engines started showing up in pickup trucks back in the 1980s and while those engines didn’t particularly wear well, fuel dilution wasn’t really a big issue.

In the 1990s, these engines really started coming into their own. Wear metals improved and the oil changes started getting longer and longer. Ford started using the Navistar 7.3L Power Stroke and Dodge used the Cummins 6BT 5.9L, and both were excellent engines. They produced a lot of power and left very little metal in the oil to show for it.

GM used the Detroit Diesel 6.5L, and while that was a good engine and a lot of them are still on the road today, it tended to make a lot more metal than its competitors. It wasn’t until GM started the Isuzu 6.6L Duramax that it really had a world- class diesel that was every bit as good as what Ford and Dodge were using.

With this new generation of engines, we started seeing people run 5,000-mile oil changes regularly, where the old standard was just 3,000 miles. And oil changes have gotten longer and longer since.

These days it’s not uncommon at all to see those engines running 10,000 miles on the oil without any special oil filtration set-up. Of course, a lot of that is dictated by the type of use they see. This was also the carefree days before emission controls starting becoming mandatory.

For some of you, the words emission controls may make you turn away in disgust and I’ll admit, on my own truck engine (a gasoline powered GM 350), the emission controls haven’t gotten the attention the rest of the engine has. But really the idea isn’t really all that bad.

Piston powered aircraft engines don’t have any emission controls on them, but those engines are plagued by rust and corrosion because condensation from the air is allowed to enter through the breather. Modern gasoline and diesel engines don’t have that problem because their crankcases are sealed to the elements and that keeps corrosion to a bare minimum. It’s also one of the reasons you don’t really need to change your oil on a time basis anymore. We get a lot of questions about if an oil will last a year or not and the answer is almost always yes, because very little corrosion builds up on these engines.

Of course, gasoline-powered engines have had emission control systems on them since the 1970s and that means the engine designers have had a lot of time to get it right. When emission controls started appearing on diesel engines in 2005 and 2006, there were a lot of growing pains with that introduction. Couple that with the fact that competition brought about the need for more and more power, and now we started seeing changes in the oil samples, mainly at fuel dilution.

We first started seeing a lot of fuel when Navistar came out with the 6.0L Power Stroke in 2003. Those engines almost always had a lot of fuel in the oil, especially when they were new¾and when I talk about a lot, I mean 4% and 5%.

We weren’t sure exactly what cased this, but it was showing up in almost every sample we saw and this presented a problem for us because we had always considered 2.0% to be an “action” level of fuel. So what do you do when every engine starts showing more than 2.0% fuel? Do you start sending every owner back to the dealer saying there’s a problem? And what do you do if you see a lot of fuel dilution, but wear metals continue to look good?

So the 6.0L Power Stroke caused us to take a different look at fuel and how much of a concern it really is. No longer could we consider 2.0% is a major problem. Now we suggest that it’s only an issue if the oil level is rising on your dipstick, or if the amount of fuel we find in each sample is increasing. As it turns out, continual fuel dilution in the oil at around 2.0% to 3.0% sometimes is from a problem, but it should not be considered a major one and I know about that first-hand.

About my Passat

In 2004 my wife and I bought a Volkswagen Passat with the 1.8L turbo gasoline engine. Almost from the start, this engine was leaving a lot of fuel in the oil and I would look at the analysis results and just shrug my shoulders. The engine was running fine and wear metals were acceptable, but the fuel mileage was never quite a good as advertised. For me, that didn’t seem like a good enough reason to tear into the fuel system.

Shortly after we bought the Passat, Volkswagen set us a letter saying they would extend the engine warranty to 10 years or 100,000 miles due to sludging problems they were having. I suspected these problems stemmed from a lot of fuel dilution in the oil coupled with really long oil runs, but I’m not sure. The kicker for the extend warranty was I had to change oil every 5,000 miles and I had to use a VW-approved oil. Of course, they approved expensive oils like Elf and Total, and those aren’t on my approved list. My list includes oils that are on sale at Wal-Mart, so I decided to stick with my oils and just change the oil at 3,000 miles. So far the plan has worked but if it fails, I’ll be writing about how I rebuilt the engine myself (twice) in my Dad’s barn.

In the end, we haven’t done anything about the continual fuel in our Passat’s oil (except curse VW), but the engine is still running fine and is close to the magic 100,000-mile mark. When we hit 100K, we’ll unload it and get my wife the new car of her dreams (a white Jaguar S-type). So despite the fuel being present in every report, really the only problem this has caused is our MPG isn’t quite what it should be.

Back to diesel engines

So anyway, the fuel dilution problems in the 6.0L Power Stroke eventually got better and those engines now look as good as any we see, so they’ve changed something to solve the fuel problem.

Then came the next generation of diesels (the 6.4L Power Stroke) and the fuel problems started up again. It’s not uncommon to sees excess fuel in over 2% of the small diesel engine samples we see today, and when it shows up that often, it’s hard to say it’s a major issue. It shouldn’t really be there, but it doesn’t necessarily warrant a trip to the dealer either.

The source of the fuel dilution differs from one engine manufacturer to the next, though injectors and emission control systems appear to be the root cause of most of these problems.

For the new 6.4L Power Strokes, if it’s not an injector it could be another part of the fuel system, like a pump. The DPF (diesel particulate filter) regeneration process will also cause fuel to show up in the oil. Does that mean these new engines are junk? Not at all. It just shows they have some growing pains to work out and once that happens, the fuel dilution problems will eventually taper off.

Until then, don’t get too excited 2.0% or more of fuel dilution, but do watch for an increased oil level on your dipstick. While you may think an engine that makes oil is like the goose that laid the golden egg, it’s really a possible sign of problems down the road. Small amounts of fuel are okay, but if the oil level is rising or if we’re seeing more and more fuel in each sample you do, fuel could be a problem.

By-Pass Oil Filtration

Want to run your oil longer than you used to? Lots of people do. We take many factors into consideration when determining your optimal oil change. Many people think choosing the right oil is important, but in reality, you can run any API-certified oil indefinitely, as long as it’s not contaminated. That’s the real key: not contaminated, with metal, solids, moisture, or fuel. So what can you do to keep your oil in pristine condition? Enter bypass filtration.

In-line oil filtration — the oil filter that comes installed from the factory — filters oil entering the engine down to roughly 30–40 microns (millionths of a meter). This is about the most the in-line system can achieve, because when the oil is cold or the filter is partially plugged, a finer filter would cause too great a pressure drop, forcing open the filter bypass valve and allowing unfiltered oil to circulate through the engine.

Bypass filtration works differently. When this type of auxiliary system is installed, some of the oil bypasses the in-line filter system, flowing though a bypass filter and then returning to the oil sump. Using this method, sump oil is constantly being cleaned any time the engine is running, and it can be filtered down to a very fine size. All you have to do to maintain the system is occasionally change the bypass filter.

Bypass filtration systems remove blow-by and oxidation products from the oil and can help reduce silicon accumulations. Having a bypass filtration system installed increases the overall sump size of the engine, helping dilute the concentration of metals in the oil. Oil does not wear out. Its usefulness is limited only by contamination. Bypass filtration removes or dilutes many of those contaminants.

Is a bypass filtration system a good move for your engine? The only way to know is to test your oil. Send us a sample and tell us you’re considering adding a bypass filter. We’ll let you know what areas of the report might see improvements and whether those improvements would be essential to run longer on your oil. Bypass systems can be helpful, though not everyone benefits from a bypass system in the same way. In general, we have found bypass systems to be helpful in keeping the oil clean.

Soot: How Much is too Much?

Blackstone offers percent soot testing as an optional test above and beyond what we do in the standard analysis. It’s something many of our diesel customers have shown interest in. It can be challenging for people to understand how much soot is a problem and how much is normal, so in this article we’ll shed some light on our testing process and what it can tell you about the health of your engine.

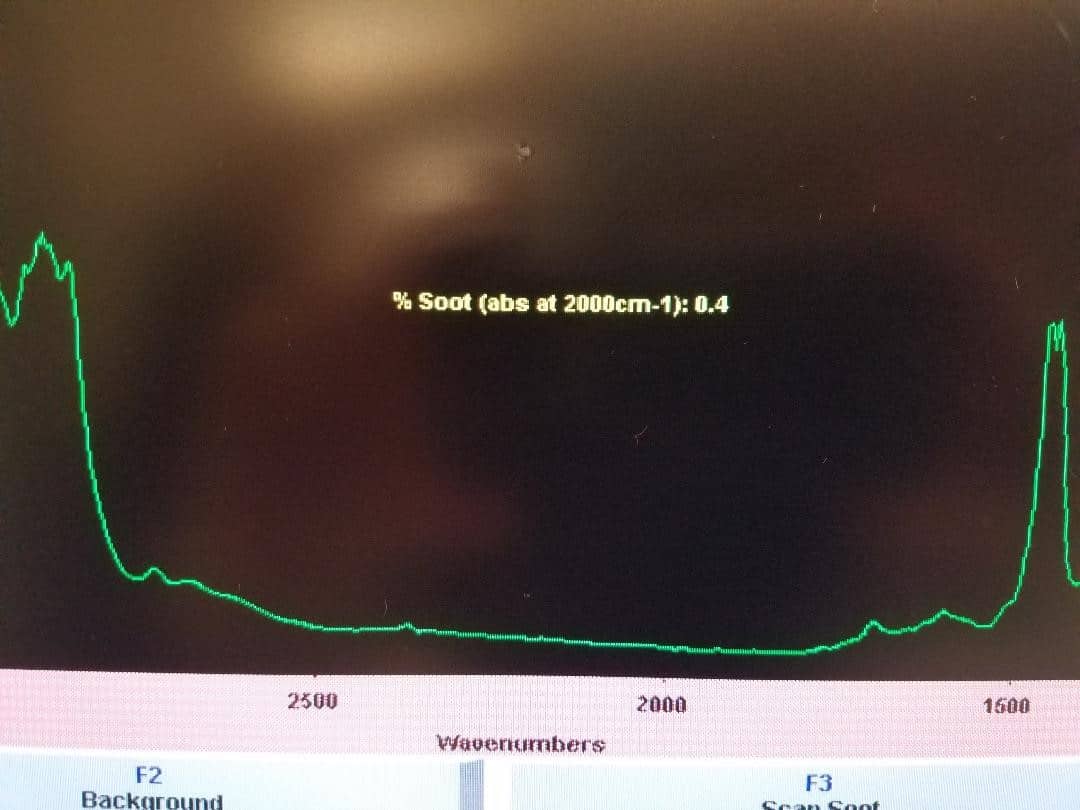

Here’s a brief run-down of how it works. We use an FTIR (Fourier Transform Infrared) spectrometer to measure the percentage of soot present in an oil sample. Essentially, soot raises the absorption rate of the infrared light spectrum and when an infrared beam is shot through the sample, the rate of absorption is measured and quantified. The lab operator ensures the machine is running properly by performing a series of check standards, including calibrating against a known 2.0% soot sample to ensure accuracy.

Okay, nap-time is over. So what is soot and what impact can it have on an engine? Soot is a natural by-product of internal combustion. Soot is the reason diesel engine oil turns black, sometimes only after a few miles. When it becomes excessive it can thicken up the viscosity, leave deposits on wearing components, and ultimately clog a filter (or perhaps worse, an oil passage). Excess soot can have an abrasive component and has the ability to stick to wearing surfaces, potentially increasing oil consumption.

A used sample from a Volkswagen 2.0L TDI. Soot reads at 0.4%.

We like to see soot at 1.0% or less; anything higher than 2.0% to be cautionary. So what does that mean to you? In layman’s terms, excess soot can indicate a combustion problem. Pinpointing that problem (or problems) can be a bit more difficult, but there are a couple fairly simple things to check if you think you’re seeing excess (or just more than normal) soot in the oil. Make sure that the fuel system is maintained and properly calibrated so that the injectors are operating at peak efficiency and with a proper air/fuel ratio. Also check for intake leaks and make sure that the air filter is clean and serviceable. Make sure injection timing is set correctly as well. Change the oil and filter regularly to prevent soot build-up.

It’s always possible that excess soot is due to a mechanical problem too, and that’s obviously a bit more involved than just changing the oil or swapping out a dirty air filter. Excessive ring clearance is a common cause of excess soot. Keep an eye on oil consumption as increases in that area can also show a developing ring problem.

Several of our customers have installed by-pass filtration systems in an effort to keep soot lower and the oil cleaner in general, and that can be effective. Employing an oil analysis regimen can also be helpful in assessing wear metals and other contamination like soot…but as a Blackstone customer, you already knew that!