How Often Should You Change Your Oil?

Change is inevitable, right? But not as inevitable as it used to be, at least for your engine oil. When it comes to the questions we get every day, right up there with “What kind of oil should I use?” is “How often should I change my oil?” Happily, the answer for most people is: Not as often as you used to.

What other people will tell you

Back in the day, everyone knew you changed your oil at 3,000 miles or three months, whichever comes first. Wait, did I say back in the day? Lots of places still tell you that’s how often to change it, and not surprisingly, the places you’re hearing this are oil change places that make money from you coming in regularly. We’re here to help cut through the noise, and hopefully you’ll believe us because hey, we’ve got science on our side. The answer to how often you need to change your oil is: It’s different for everybody.

Owner’s manual

Most cars and trucks (motorcycles, boats, etc.) have guidelines listed in the owner’s manual that outline certain driving conditions and how often to change the oil.

The problem is, sometimes the conditions they outline as “severe” are laughable. We’ve seen manuals that say if you’re doing primarily city driving, that’s severe. Call me silly, but I’d say “severe” should count as something that’s out of the ordinary for most people. Most people drive to work and back. Most people drive to the store, go to school, take the kids to school, whatever.

Severe operation, on the other hand, could legitimately be something like lots of operation on dusty roads, towing constantly, driving really fast in a really hot or really cold place, or driving up and down mountain passes. Under these conditions, we could see needing to change the oil more often. But again, it really is a case-by-case thing. City driving for me, in Fort Wayne, Indiana, is different from city driving in LA.

The point is, despite the best intentions of the people who write the guidelines, how often you should change your oil really depends on you, your engine, how you drive, and where you drive. One caveat: As long as your engine is under warranty, you should change however often the manufacturer says to. That way if something goes wrong, they can’t blame you for lack of maintenance.

OLM

Most new engines also come with an oil life monitor to tell you when to change the oil. This is a good system, and even if it’s not 100% accurate all the time, it’s better than the 3,000 miles or three months system.

Different oil life monitors take different things into account. We’ve been told that certain German automakers changed from basing theirs on variables such as cold starts and RPMs to basically counting down the amount of fuel used. Some have a sensor in the oil that estimates particulates in the oil. Some monitors seem to give better recommendations the longer you use them. All this is fine and it’s better than nothing, but there’s also oil analysis. Guess which method we like best for determining how often you should change the oil?

What we look at

When you send in a sample, we ask on the oil slip if you’re interested in extended oil use. What we want to know is, do you want to run your oil longer than you currently are? We have found that people are often changing their oil too soon. As you know there is not one oil-change interval that’s perfect for everyone, so what do we take into account when we do recommend longer oil changes?

Metal

If you’ve seen our report, you know that we keep a database of all different engine types. We average their wear and then compare that to your sample to see what’s reading high, what’s normal, and what’s better than most. We like it when you send along notes. The more you tell us about how you’re driving or any specific conditions that might affect the sample, the better the recommendation we can give you.

If wear is above average, we always look for reasons that might explain why. For example, say your metals are generally higher than average but you’re also running your oil longer than average. We take that into account and give you an estimate on how much longer we think you can go for the next oil change.

If wear is above average, we always look for reasons that might explain why. For example, say your metals are generally higher than average but you’re also running your oil longer than average. We take that into account and give you an estimate on how much longer we think you can go for the next oil change.

We don’t like to take too big of a leap. We wouldn’t, for example, tell you to go from 5,000 to 10,000 miles because you might send in a 10,000-mile sample and have lots of wear, and we wouldn’t know where the tipping point was. But we might tell you to go 7,500 miles next, and if things look good at that point, to go longer after that.

Some people automatically think having more wear than average is bad, but that’s not necessarily so. If there’s a good reason for the wear, and if there’s not so much metal that it’s making the oil itself abrasive, we’re happy to let a little extra metal ride. The question is, are you okay with it? In the end our recommendation is just our opinion, and you should do whatever you’re comfortable with.

Sometimes we suspect a problem and we’ll recommend a shorter oil change. Obviously shorter oil changes don’t fix a problem if one exists, but they do let you monitor the problem more closely and get the extra metal out of the system. Once a lot of wear builds up, the oil itself can become abrasive, which causes even more wear. It’s a cycle to avoid.

Contamination

We also look at any contamination that might be present in the oil. Obviously no contamination is the best, but your engine can tolerate small amounts of fuel and (sometimes) moisture without it being a serious problem.

Fuel is actually a very common contaminant. It mainly comes from normal operation and idling, and as long as it’s not causing any wear problems, we usually would recommend a longer oil run even with fuel present. But if fuel persists or the trend is one of increasing fuel with each oil change, we’d probably recommend cutting back on your oil changes for the reasons outlined above.

We don’t see water very often because modern engines are closed up tight. But we do see antifreeze, and when it’s present we almost always recommend changing the oil more often. Antifreeze destroys the oil’s ability to lubricate parts, which is why it starts causing poor wear so soon (usually bearing wear).

We also look at how oxidized the oil is with the insolubles test. Oil oxidation happens normally and for the most part, your oil filter removes the oxidized solids from the system just fine.

Occasionally something (excessive heat, contamination) causes the oil to oxidize faster than usual and the oil filter can’t keep up. In this case we would also recommend a shorter oil change, at least until you can figure out why it’s happening.

The insolubles test also helps us determine soot problems for diesel engines. If soot is excessive but everything else looks okay, we might suggest trying a longer run. Or if there is ring wear and other signs of poor combustion, we would probably tell you to cut back.

Operation

How you drive is another factor we take into account when we suggest your next oil change interval. If you and I both have the exact same Subaru engine except you go to the track regularly and all I do is drive to work and the store, then you might get a different recommendation than me. Or maybe you won’t — if your engine looks good and it’s faring well under the racing conditions, we might be running the same oil changes.

Or, if someone tells us their commute is a long highway drive every day, that person may be able to go a lot longer on their oil than someone with the same engine who drives two miles each way to work and back every day. It’s all in the numbers. The numbers don’t lie!

What about the oil?

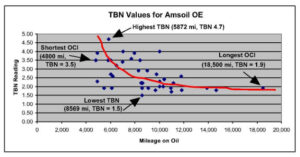

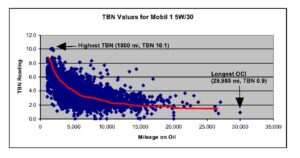

Notice what we have not said we take into account: the brand you’re using and whether it’s synthetic or petroleum oil. When Jim started this company back in 1985 he came up with a line he liked to use: Oil is oil. We still stand by that today. The oil guys would have you believe otherwise, but brand really does not seem to make a difference in how your engine wears, or how often you can change your oil.

Well, okay, if you were using some guy’s oil that he “recycled” in the back of his garage from emptied-out oil pans that he filtered with a piece of cheesecloth, we might say in that case brand does matter. But as long as you’re using an API-certified oil, your engine probably isn’t going to care what you use. We like synthetics and we like conventional oil. In the end, what you use and how often you change your oil is completely your choice. We’ll give you our recommendation and you can do whatever you want with it. If you want to run longer on the oil despite having high wear, that’s totally fine. And if you have great numbers and you like changing at 3,000 miles, that’s perfectly fine too. It’s your engine, your money, and your life: change it when you want!

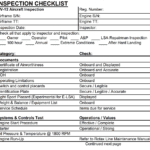

This year has been different, but it’s not really the plane’s fault. My wife and I started the inspection in mid-July, when the weather was nice and there was still plenty of year left, but didn’t get it completely done until just last weekend (the end of January). Again, the plane is still fairly new (only at 46 hours now), so there really weren’t that many problems to address. No, this year the problem was with me. Life and work tend to have a way of keeping you busy and this year it’s been a struggle to string a few weeks together to do the inspection.

This year has been different, but it’s not really the plane’s fault. My wife and I started the inspection in mid-July, when the weather was nice and there was still plenty of year left, but didn’t get it completely done until just last weekend (the end of January). Again, the plane is still fairly new (only at 46 hours now), so there really weren’t that many problems to address. No, this year the problem was with me. Life and work tend to have a way of keeping you busy and this year it’s been a struggle to string a few weeks together to do the inspection.

Unless you suspect a problem, a short-run filter inspection would also be of minimal value, for the same reason—there really isn’t enough time for any significant metal to accumulate. So how about a situation where you are halfway through a typical oil change? Where you have enough time on the oil for an analysis to tell you something, but not enough time that the oil really needs to be changed? For situations like that, you might want to get an oil sample by pulling one up via the dipstick tube. We sell a pump for just

Unless you suspect a problem, a short-run filter inspection would also be of minimal value, for the same reason—there really isn’t enough time for any significant metal to accumulate. So how about a situation where you are halfway through a typical oil change? Where you have enough time on the oil for an analysis to tell you something, but not enough time that the oil really needs to be changed? For situations like that, you might want to get an oil sample by pulling one up via the dipstick tube. We sell a pump for just