Under Pressure! (Part 2)

In Part 1 of this saga, our flying club’s newly installed O-360 lost oil pressure in flight with a student pilot at the controls. After a brief landing then an immediate a go-around (you read that right), and a fair amount of sweat and tears – but fortunately no blood – we found the engine had digested an errant paper towel, which was blocking the suction screen.

Crud in the pan

The hard part begins

Now that we knew the engine actually did suffer a loss of oil pressure (it wasn’t just the gauge) and the filter analysis showed that some damage had been done, our next step was to figure how to proceed.

We consulted as many experts as we could and received suggestions ranging from “just go fly it” to “pull a cylinder and look for damage” to “overhaul it” and everything in between. The jury was out, and we had to decide whose suggestion to follow.

Lycoming has a convenient Service Bulletin about what to do if you find metal in the oil filter, so we started there. Service Bulletin 480F suggested, based on the amount and size of metal in the oil filter, that we remove the oil pan and check for metal. That seemed like a good idea; not only were we still troubleshooting mechanical wear, but also, we didn’t know how much paper towel was still in the engine.

It took two solid days of work to remove, inspect, clean, and reinstall the oil sump, which still had paper towel in it. Once that was done, after finding no large pieces of metal in the sump and being sure there weren’t any leftover paper towels in the engine, we did a 30-minute ground run then drained the oil, and cut the filter to check for metal.

Intestinal fortitude

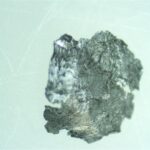

The oil analysis was unremarkable, but the oil filter report noted 10-15 non-ferrous metallic flakes per pleat with a few dozen larger pieces that had scrape marks on them. So – a little better than

Metal from the filter, magnified in analysis

before, but certainly not clean. But this was only a 30-minute ground run compared to the 20-some hour sample. Were the improvements from the shorter oil change, or an actual improvement? We didn’t know.

Now, I’ve been an analyst at Blackstone for over a decade. I’ve helped countless customers diagnose their own engine issues and told people to go fly it and check back. But there isn’t any amount of intestinal fortitude that prepares someone for the reality of experiencing a problem, diagnosing engine damage, doing what you can to fix it, and know that the next step is to go flying and see how it goes.

The two A&Ps on the field agreed that if we made it past the first 10 hours (if) without any oil pressure issues, then we should be fine. “But watch that oil pressure,” they cautioned.

Going up

We took all the precautions we could: we went up in pairs (so one person could watch the oil pressure), we selected calm days, affording us four runway options for an emergency landing, and we stayed within glide distance of the airport for 10 long hours.

I am glad to say that those first 10 hours were uneventful. Oil pressure remained strong, the engine ran great, and we had no issues. With each hour that passed, our confidence grew, so we eagerly sent another oil and filter sample for analysis, hoping for hard data to bolster our confidence.

The oil analysis was unremarkable, but the filter – not great. Approximately 30 variously sized non-ferrous flakes were present per pleat, along with one piece of steel.

Not what you want to see

This wasn’t what we were hoping for, but this oil run was 10 hours long as opposed to the previous 30-minute ground-run sample. There was bound to be more metal, right? Regardless, there was still more metal after 10 hours than there was in our previous 50-hour samples, so we weren’t in the clear yet.

Our solution? Do another 10-hour oil run for an apples-to-apples comparison. At this point, with 10 hours of uneventful flying under our belt, our confidence was starting to grow, so we ventured out a little from the airport environment. After 10 hours, we sent the oil and filter for analysis, fairly confident that this second sample would reveal the improvement that was bound to come.

Instead, we received the disheartening news that “the overall quantity and size of the non-ferrous flakes was similar to the previous filter.” Dang.

Hard discussions

We debated what to do next. Are we throwing money away on oil and filters when we might need an overhaul anyway? Do we keep wasting filters when the nationwide filter shortage might ground us anyway? Do we run 25 hours, despite not seeing an improvement in the metals?

We reconsidered an earlier suggestion to pull a cylinder and look for crank/bearing damage, but that might raise more questions than answers: what should a 1500-hour crank/bearing look like? How will we know if the damage is excessive without pulling all four cylinders and comparing? And at that point why not just overhaul?

Opinions varied among our club members. One thought we were overreacting and that a paper towel couldn’t cause engine damage. Others of us were more cautious, remembering how little metal our engine used to make in 50 hours. As a group, we exchanged some vibrant text conversations as we decided how to proceed.

With our concern about irreversible, ongoing damage, we opted to do another short 10-hour oil change to try and limit further damage and get another good comparison to gauge progress. I was afraid that if this sample didn’t come back cleaner, we’d start considering exploratory surgery and watch the summer tick by from the ground.

Baby steps

We knocked those 10 hours out in less than a week and had results early the following week. I jokingly told my coworker that I’d bribe him with beer if he gave us a good enough report that we wouldn’t have to ground the aircraft for the summer.

Still with the metal

As it turned out, no bribery was needed: the oil analysis came back clean and the filter report contained good news: less metal than before. Finally! Maybe everything was going to be okay. Granted, we’re not totally out of the woods yet – we’re still monitoring and we’re going to change the oil in 25 hours, but at least we’ve got data that suggests we’re past the worst of it. If the numbers are good in 25 hours, then we’ll try 50. That night of the improved report was the best night’s sleep I’d gotten in months.

Lessons learned

Hindsight is always 20/20, as they say, but looking back I think there are several lessons to be learned.

First, when you’re troubleshooting a problem, do your research and get as much data as you can. It honestly shocked me how many different opinions we received. At one point I called Lycoming. They called me back several days later, and after listening to my story the tech said we needed an overhaul.

I replied, “Well in the week I was waiting for you to get back to me, we did a 30-minute ground run, tested the oil and filter, and we’ve since flown a couple of uneventful hours, as per SB 480 and we’re planning on flying a total of 10 hours before retesting.”

He said, “Okay, that’s good. Do that and proceed as planned.”

In less than five minutes he went from telling me to overhaul to “go fly.” There’s a vast dichotomy there. I get that there’s a lot of liability in aviation, but that just makes it harder to make good, educated decisions. We did a lot of research, gathered data, and consulted with as many people as we could to make the best decision for us. Do your homework.

Second, remember that you have many tools in your toolbox for diagnosing problems. Our oil reports came back clean all along – it was the filter analysis that was showing metal. Oil analysis measures the microscopic particles in the oil; the filter/screen is where you’ll see visible metal. Always cut your filter open, and use oil analysis in conjunction with other tests (like borescope and compression checks). The more data you have, the better decision you can make.

Third, as we said last time – trust your gut. If your intuition tells you something is wrong, don’t ignore it. But the reverse is also true: after all those hours of flying the pattern with strong oil pressure, good RPMs, and normal oil temps, we had a strong feeling that our engine was going to be okay – we just had to wait a few oil changes for the data to support our intuition.

And last but certainly not least – keep the damn paper towels far away from your engine!