This article, by Mike Busch, originally appeared in the March 2010 issue of Sport Aviation as part three in the series “Reliability-Centered Maintenance.” We are reprinting it with the permission of the author.

To properly apply reliability-centered maintenance (RCM) principles to the maintenance of our piston aircraft engines, we need to analyze the failure modes and failure consequences of each major component part of those engines.

In this article we’ll examine the critical components of these engines, how they fail, what the consequences are of those failures on engine operation and safety of flight, and what sort of maintenance actions we can take to deal with those failures effectively and cost-efficiently.

Crankshaft

It’s hard to think of a more serious piston engine failure mode than a crankshaft failure. If it fails, the engine quits. Yet crankshafts are rarely replaced at overhaul. Lycoming says their crankshafts often remain in service for more than 14,000 hours and 50 years! TCM hasn’t published this sort of data, but TCM crankshafts probably have similar longevity.

Crankshafts fail in three ways: 1) infant-mortality failures due to improper material or manufacture, 2) failures following unreported prop strikes, and 3) failures secondary to oil starvation and/or bearing failure.

We’ve seen a rash of infant mortality crankshaft failures in recent years. Both TCM and Lycoming have had major recalls of crankshafts that were either forged from bad steel or were physically damaged during manufacture. Those failures invariably occurred within the first 200 hours after a newly manufactured crankshaft entered service. If a crankshaft survives the first 200 hours, we can be pretty confident that it was manufactured correctly and should perform reliably for many engine TBOs.

Unreported prop strikes seem to be getting rare because owners and mechanics are becoming smarter about the high risk of operating an engine after a prop strike. Both TCM and Lycoming state that any incident that damages the propeller enough that it has to be removed for repair warrants an engine teardown inspection. This applies even to prop damage that occurs when the engine isn’t running. Insurance will pay for the teardown and any necessary repairs, no questions asked, so it’s a no-brainer.

That leaves us with failures due to oil starvation and/or bearing failure. We’ll talk about these when we look at oil pumps and bearings.

Crankcase

Crankcases are also rarely replaced at major overhaul, and they often provide reliable service for many TBOs. If the case stays in service long enough, it will eventually crack. The good news is that case cracks propagate slowly, so a detailed annual visual inspection is sufficient to detect such cracks before they pose a threat to safety. Engine failures caused by case cracks are extremely rare.

Camshaft and lifters

The cam/lifter interface endures more pressure and friction than any other moving parts in the engine. The cam lobes and lifter faces must be hard and smooth in order to function and survive. Even tiny corrosion pits (caused by disuse or acid build-up in the oil) can lead to rapid destruction (spalling) of the cam and lifters and the need for a premature teardown. This is the number one reason that engines fail to make TBO. This problem mainly affects owner-flown airplanes because they tend to fly irregularly and sit unflown for weeks at a time.

Camshaft and lifter problems seldom cause catastrophic engine failures. The engine will continue to make power even with severely spalled cam lobes that have lost a lot of metal, although there is some small loss of power. Typically, the problem is discovered when the oil filter is cut open and found to be full of metal.

If the oil filter isn’t cut open and inspected on a regular basis, the cam and lifter failure may progress undetected to the point that ferrous metal circulates through the oil system and contaminates the engine’s bearings. In rare cases, this can cause catastrophic engine failure. A program of regular oil filter inspection and oil analysis will prevent such failures.

If the engine is flown regularly, the cam and lifters can remain in pristine condition for thousands of hours. Some overhaul shops routinely replace the cam and lifters with new ones at major overhaul, but other shops use reground cams and lifters and most knowledgeable engine experts agree that properly reground cams and lifters are just as reliable as new ones.

Gears

The engine has lots of gears: crankshaft and camshaft gears, oil pump and fuel pump drive gears, magneto and accessory drive gears, prop governor drive gears, and sometimes alternator drive gears. These gears typically have a very long useful life and are not usually replaced at major overhaul unless obvious damage is found. Gears rarely cause catastrophic engine failures.

Oil pump

Failure of the oil pump is occasionally responsible for catastrophic engine failures. If oil pressure is lost, the engine will seize quite quickly. The oil pump is very simple, consisting of two gears in a close-tolerance housing, and is usually trouble-free. When trouble does occur it usually starts making metal long before complete failure occurs. Regular oil filter inspection and oil analysis will normally detect oil pump problems long before they reach the failure point.

Bearings

Bearing failure is responsible for a significant number of catastrophic engine failures. Under normal circumstances, bearings have a very long useful life. They are always replaced at major overhaul, but it’s quite typical for bearings that are removed at overhaul to be in excellent (sometimes even pristine) condition with very little measurable wear. Bearings fail prematurely for three reasons: (1) they become contaminated with metal from some other failure; (2) they become oil-starved when oil pressure is lost; or (3) they become oil-starved because the bearing shells shift position in the crankcase saddles to the point where the bearing’s oil supply holes become misaligned (“spun bearing”).

Contamination failures can be prevented by using a full-flow oil filter and inspecting the filter for metal on a regular basis. So long as the filter is changed before its filtering capacity is exceeded, particles of wear metals will be caught by the filter and won’t contaminate the bearings. If significant metal is found in the filter, the aircraft should be grounded until the source of the metal is found and corrected.

Oil starvation failures are fairly rare. Pilots tend to be well-trained to respond to loss of oil pressure by reducing power and landing at the first opportunity. Bearings will continue to function properly even with fairly low oil pressure (e.g., 10 psi).

Spun bearings are usually infant mortality failures that occur either shortly after an engine is overhauled (assembly error), or shortly after cylinder replacement. Failures can also occur after a long period of crankcase fretting (which is detectable through oil filter inspection and oil analysis), or after extreme cold-starts without proper pre-heating. These are usually random failures, unrelated to hours or years since overhaul.

Connecting rods

Connecting rod failure is responsible for a significant number of catastrophic engine failures. When rod fails in flight, it often punches a hole in the crankcase and causes loss of engine oil and subsequent oil starvation. Rod failures have also been known to result in camshaft breakage. The result is invariably a rapid loss of engine power.

Connecting rods usually have a very long useful life and are not normally replaced at major overhaul. (The rod bearings, like all bearings, are always replaced at overhaul.) Some rod failures are infant mortality failures caused by improper torque of the rod cap bolts. Rod failures can also be caused by failure of the rod bearings, and these are usually random failures unrelated to time since overhaul.

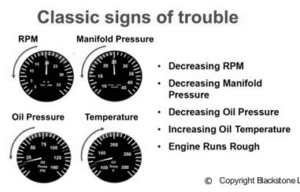

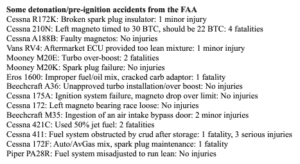

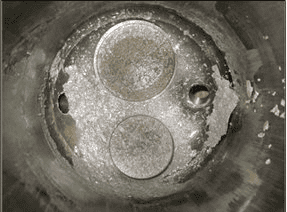

Pistons and rings

Piston and ring failures can cause catastrophic engine failures, usually involving only partial power loss but occasionally total power loss. Piston and ring failures are of two types: (1) infant mortality failures due to improper manufacture or installation; and (2) heat-distress failures caused by pre-ignition or destructive detonation events. Heat-distress failures can be caused by contaminated fuel or improper engine operation, but they are generally unrelated to hours or years since overhaul. Use of a digital engine monitor can usually detect pre-ignition or destructive detonation episodes and allow the pilot to take corrective action before heat-distress damage occurs.

Cylinders

Cylinder failures can cause catastrophic engine failures, usually involving only partial power loss but occasionally total power loss. A cylinder has a forged steel barrel mated to an aluminum alloy head. Cylinder barrels normally wear slowly, and excessive wear is detected at annual inspection by means of compression tests and borescope inspections. However, cylinder heads can suffer fatigue failures, and occasionally the head can separate from the barrel, causing a catastrophic engine failure. Cylinder head failures can be infant mortality problems (due to improper manufacture) or can be age-related. Age-related failures seldom occur unless the cylinder is operated for more than two or three TBOs. Nowadays, most major overhauls include new cylinders, so age-related cylinder failures have become quite rare.

Valves and valve guides

It is quite common for valves and guides (particularly exhaust) to develop problems well short of TBO. Valve problems can usually be detected prior to failure by means of compression tests, borescope inspections, and surveillance with a digital engine monitor (provided the pilot knows how to interpret the engine monitor data). If a valve fails completely, a significant power loss can occur.

Rocker arms and pushrods

Rocker arms and pushrods (which operate the valves) typically have a very long useful life and are not routinely replaced at major overhaul. (Rocker arm bushings are always replaced at overhaul). Rocker arm failure is quite rare. Pushrod failures are caused by stuck valves and can almost always be avoided through repetitive valve inspections and digital engine monitor usage, as discussed earlier.

Magnetos

Magneto failure is uncomfortably commonplace. Fortunately, aircraft engines are equipped with dual magnetos for redundancy, and the probability of both magnetos failing simultaneously is extremely remote. Mag checks during pre-flight run-up can detect gross magneto failures, but in-flight mag checks are far better at detecting subtle or incipient failures. Digital engine monitors can reliably detect magneto failures in real time if the pilot knows how to interpret the data. Magnetos should be disassembled, inspected, and serviced every 500 hours—doing so drastically reduces the likelihood of an in-flight magneto failure.

The bottom line

The “bottom-end” components of these engines—crankcase, crankshaft, camshaft, bearings, gears, oil pump, etc.—are very robust. They normally exhibit very long useful lives that are many times as long as recommended TBOs. Most of these bottom-end components (with the notable exception of bearings) are reused at major overhaul and not replaced on a routine basis.

When these items do fail prematurely, the failures mostly occur shortly after engine manufacture, rebuild, or overhaul, or they are random failures that are unrelated to hours or years since overhaul. The vast majority of random failures can be detected long before they get bad enough to cause catastrophic engine failure simply by means of routine oil filter inspection and laboratory oil analysis. There seems to be no evidence that these bottom-end components exhibit any sort of well-defined steep-slope wear-out zone that would justify fixed-interval overhaul or replacement at TBO.

The “top-end” components—pistons, cylinders, valves, etc.—are considerably less robust. (The “top end” of a piston engine is analogous to the “hot section” of a turbine engine.) It is not unusual for top-end components to fail prior to TBO. However, most of these failures can be prevented by regular inspections (compression tests, borescope, etc.) and by use of digital engine monitors (by pilots who have been taught how to interpret the data). Furthermore, when potential failures are detected, the top-end components can be repaired or replaced quite easily without the need for engine teardown. Once again, the failures are mostly infant-mortality failures or random failures that do not correlate with time since overhaul.

The bottom line is that a detailed failure analysis of piston aircraft engines using RCM principles strongly suggests that what the airlines and military found to be true about turbine aircraft engines is also true of piston aircraft engines: The traditional practice of fixed-interval overhaul or replacement is counterproductive. A conscientiously applied program of on-condition maintenance that includes regular oil filter inspections, oil analysis, compression tests, borescope inspections, and in-flight digital engine monitor usage can be expected to yield improved reliability and much reduced maintenance expense and downtime.

Magnetos are an exception. They really need to go through a fixed-interval major maintenance cycle every 500 hours, because we have no effective means of detecting potential magneto failures without disassembly inspection.