TBN/TAN: Do You Need One?

What exactly is a TBN or TAN, and do you really need one?

“Do I need a TBN?” It’s a question that comes up a lot. The TBN is a test we do on engine oil, while the TAN is meant for transmissions and other gear lubes or hydraulic oils. These tests are widely discussed on internet forums, where facts and misconceptions can be hard to distinguish. So let’s dig into the science behind them!

What is a TBN or TAN?

The Total Acid Number and Total Base Number are ways to determine how acidic oil has become (TAN), or how effectively it can neutralize the acids that form from combustion and other factors (TBN). An increasing TAN indicates more acidity, while a decreasing TBN shows an oil’s acid-neutralizing additives are being used up. You may remember the pH scale from science class. pH is a more familiar measure of acidity in everyday life. So why don’t we use pH on oil?

pH stands for “potential of hydrogen” and measures the flow of hydrogen ions in a water-based solution. pH doesn’t apply to oil because these ions can’t flow through oil – it’s a poor conductor. That’s why oil is used as an insulator for transformers and other applications that call for interrupting the flow of electrical current. Fortunately, we can use titration to get around this obstacle. Titration is used to determine the concentration (in this case, the acidity level) of an unknown solution (oil) by exposing it to measured quantities of a known solution (acid or base).

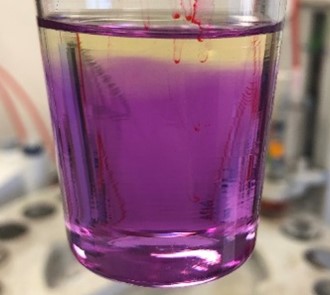

Running the tests

We start by mixing one gram of oil with a happy blend of toluene, chloroform, isopropyl alcohol, and a splash of H2O. (Kids, don’t try this at home!) The solvent breaks down the oil into a solution that is a better conductor, so we can measure the pH. The next step differs slightly for the TAN or TBN.

For the TAN, we add a cocktail of chemicals – let’s call it Bruce – to the toluene solution, a little at a time. This continues until the pH reaches 11. The lab techs then use an equation to calculate the TAN from the amount of Bruce added to the oil-toluene blend.

The TBN follows a similar methodology, except the solution added is more acidic – more of a Boris than a Bruce.

The end goal for the TBN titration is a pH of 3, and as with the TAN, the lab people are doing some math to transform the amount of Boris added to the oil into your TBN number.

Why get a TBN?

As the oil circulates through the harsh environment of a hot, running engine, combustion causes acids to form. These acids can cause increasing wear and corrosion. To prevent this, the oil manufacturers add detergent additives to the oil, which help it buffer those acids and stabilize the oil’s pH. The higher the TBN, the better your oil can resist becoming acidic. That’s the main reason to check the TBN. It’s a helpful data point if you want to extend your oil change interval beyond manufacturer recommendations.

The TAN does essentially the same thing, but we use the TAN on oils that don’t have detergent additives (like hydraulic oil and ATF). Some industrial equipment manufacturers will set standards for when to change the oil based on the TAN.

Which oil has the highest TBN?

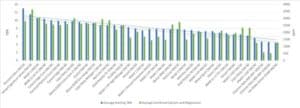

The TBN is mainly based on the amounts of calcium and magnesium (detergent additives) in the oil. Oils with more of those additives typically have a higher starting TBN, and those with less will rank lower on the list. Is more better? Not necessarily (and we’ll get into that a little later). Meanwhile, Figure 1 lists a slew of virgin engine oils and their average starting TBNs, from highest to lowest. The progression isn’t perfectly consistent, because we don’t test for every conceivable substance the oil manufacturers might include that determines the TBN.

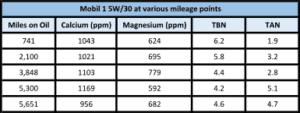

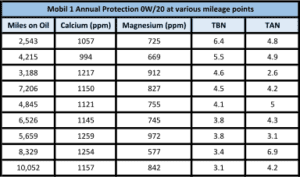

As you probably know, the TBN drops pretty fast when you start using the oil. Then it levels out and drops more slowly, the longer the oil is run. Figures 2 and 3 show two types of Mobil and how the TBN tends to fall as acidic substances start to “use up” the detergent additives. That’s what they’re there for, and we consider any TBN over 1.0 sufficient, while a TBN of 2.0 or greater is ideal when choosing to run the oil longer than you currently are. Note that ppm calcium and magnesium stay roughly the same – it’s their ability to neutralize acids that decreases.

Figure 2: This oil has an average starting TBN of 7.5. Note the roughly inverse relationship of the TBN and TAN readings; as the TBN decreases, the TAN increases, as less “active additive” is available to neutralize acids.

Figure 3

Figure 3: This oil has an average starting TBN of 7.9. The chart shows the same fairly predictable drop in TBN as miles increase. Interestingly, the TAN is less predictable, probably due to factors outside the scope of this newsletter.

Is more better? A look at two novel blends

It’s easy to see how you might feel like you want an oil with a starting TBN that’s as high as possible. But Figure 1 makes it clear that oils with all sorts of starting TBNs are available. Did the manufacturers at the low end of the scale just cheap out on additive? Not at all. Oil manufacturers have to cater to an array of unique engine designs, operating conditions, etc. As technology evolves, so does oil.

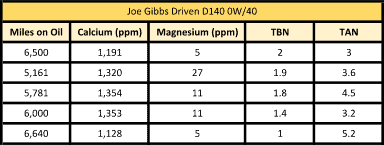

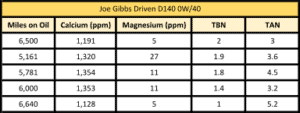

Joe Gibbs

See, for example, Figure 4, which lists a few different samples of Joe Gibbs Driven D140 oil. It had the lowest average starting TBN (4.4) thanks to fairly low levels of calcium and magnesium. This left the TBN between 2.0 and 1.0 after just 5,000-6,000 miles. But the engine that produced those numbers was a Porsche 911 that had excellent wear trends (see Figure 5). This oil is specifically formulated with lower calcium and higher moly to combat low speed pre-ignition and reduce abnormal combustion and wear. While we can’t say whether this oil really does reduce LSPI, it seems to work as well as others do and we see no problems with the novel additive blend.

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 5: Wear trends for the five samples in Figure 4 (and one additional sample, not included there because TBN and TAN were not requested). Wear is consistent over time and compares favorably to averages, despite the low TBNs.

Chevron Delo

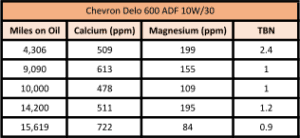

Chevron Delo 600 ADF is another oil that breaks the traditional additive mold, and it’s fairly new to the market. The 15W/40 and 10W/30 formulations hold the 2nd and 3rd place spots for lowest starting TBN in Figure 1, which is surprising, since they’re formulated for diesel engines – diesel oil tends to have more dispersant additive than oil designed for gasoline engines (most of the oils in Figure 1 are gas engine oil). Figure 6 shows the Delo 600’s TBN reaching our “1.0 limit” starting around 9,090 miles. Chevron also had particular goals in mind for this oil – it uses “ultra-low ash additive technology” and is meant for engines with SCR and EGR emissions systems that need to meet state emissions standards.

Figure 6

Figure 6: This oil had an average starting TBN of 4.7. The chart shows the low levels of calcium and magnesium that resulted in fairly low TBNs after typical oil runs for diesel engines.

Since additive packages tend to be proprietary and Chevron never did respond to my email, we can only speculate as to how the elements we find in our testing relate these constraints. Maybe such low calcium and magnesium reflect a reduction in calcium sulfonate and magnesium sulfonate (the compounds that register as calcium and magnesium). While these compounds work well as detergent/dispersants and their alkalinity helps buffer acids, their presence would also boost the sulfur content – a potential problem for emissions goals. But the additive package is unique in other ways too.

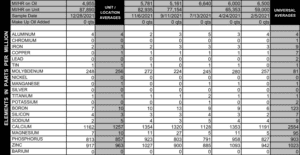

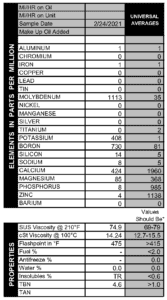

Figure 7

Figure 7 is a virgin sample of Chevron Delo 600 ADF 15W/40. Note the high levels of molybdenum, potassium, and boron, and low levels of phosphorus and zinc, in contrast to the more typical additive package shown in the universal averages column. Moly seems to be providing most of the anti-wear properties that phosphorus and zinc ordinarily would. Potassium is noteworthy and caught our attention right away, since it’s one of two potential markers for anti-freeze.

We’re not certain what additive compound registers as potassium in this oil, but because potassium is alkaline, perhaps it performs some of the same functions calcium sulfonate and magnesium sulfonate do in more traditional additive packages.

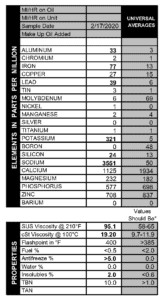

Interestingly, even when potassium (and sodium, which is also alkaline) is truly from coolant contamination, it can skew the TBN. Figure 8 is an example of an engine suffering from coolant contamination, which is taking a heavy toll on the bearings and physical properties of the oil. An oil change (and probably major repairs) are needed, yet out of context, the 10.0 TBN looks great. But that doesn’t mean the oil is ready for more use; rather, coolant is skewing the reading. That’s why we never judge a used oil sample by a single data point!

Figure 8

Figure 8 shows a sample of Valvoline 10W/30, which has an average TBN of 7.2 out of the bottle. The oil was used 3,000 miles in an engine with a major coolant problem, seen in very high levels of potassium and sodium, a thick viscosity, high insolubles, and high wear levels. The TBN is very high at 10.0, but that doesn’t mean the oil is ready for more use; rather, coolant is skewing the reading.

As for Chevron 600 ADF? The jury is still out on what kind of results this oil will produce over time, since most of the samples we’ve tested so far are from young engines going through wear-in. It will be interesting to see how these engines mature, but we suspect in the end, this unique oil will perform as well as any other in the most crucial ways: lubricating, cleaning, and cooling engine parts. We’ll just have to give it some special treatment on our end, to avoid false positives for anti-freeze, and avoid putting too much stock in “low” TBNs.

We hope you’re walking away armed with knowledge and a pretty good idea whether adding a TBN or TAN is going to serve your particular aims. If you’re wanting to extend your oil changes, go for it! If you just want a basic assessment of how your engine and oil are holding up, not to worry! We can provide that with the core tests in the standard analysis. Stay tuned for Part 2 next newsletter, where we venture into the lab, and learn about the effects of heat on TBNs and TANs.

Related articles

A New Wave

Saying goodbye to my 1984 Chevy

TBNs & TANs: Part 2

Determining how heat affects the TBN and TAN of the oil

Finishing the RV-12

The last article in our series on finishing the RV-12

In the Thick of it!

Five cities, five days, 5000+ cars: the 2024 Hot Rod Power Tour!