The Fuel Experiment

We experiment with fuel contamination so you don't have to!

When I first started at Blackstone, one of the contaminants that intrigued me the most was fuel. I guess I don’t know why finding fuel in people’s oil surprised me. Maybe I thought fuel and oil were separated by a giant wall somewhere in the engine. Or maybe (probably) I really didn’t understand engines very well to begin with and that only served to fuel (ha!) my interest in the contaminant.

We test for fuel using the Cleveland Open Cup method. Basically, we record the temperature at which the vapors from the oil ignite. All oils have a specification for what the flashpoint should be. When it’s lower than that, it’s because a contaminant is present. About 98% of the time, that contaminant is fuel (sometimes a solvent or refrigerant will lower a flashpoint, but rarely in gas or diesel engines). Basically, the lower the flashpoint, the more fuel you’ve got.

We can accurately measure fuel down to less than 0.5%, so that’s the lowest fuel measurement you’ll see on your report. The upper limit of what we can accurately read is 10.0%. If you’ve got more fuel than 10.0%, you’ve got bigger problems to worry about than the actual quantity of fuel in the oil.

When the opportunity came up to write an article for the newsletter, I readily accepted and already knew I wanted to write about fuel. In fact, I was not just going to write about it–I was going to get to the bottom of it. I was going to discover what causes fuel dilution and what causes fuel to disappear.

The plan

The guinea pig was my trusty Kia Optima (2.4L, 4 cylinder). I use my Kia mostly as a daily driver, traveling about seven miles to and from work each way. I love to travel and occasionally I get in a trip to Wisconsin or Iowa. By the time I started my quest to debunk fuel, I’d done a few samples with my Kia and only a trace of fuel had ever turned up so I didn’t have any known fuel system problems to contend with.

I decided to take the highway route home every day to ensure that every day I would cook out any extra fuel that was present in my oil. My 40-minute drive consisted of some city streets with a few stoplights at the beginning and end of my trip, and mostly sustained highway speeds through the middle of my trip.

Start your engines

The first thing I wanted to test was how much fuel entered the oil simply from starting the engine. Many people believe that starting an engine is one of the most taxing and wear-producing events throughout the engine’s life. To make that process easier, engines tend to start slightly rich (more fuel, less air). So, I set out to find out exactly how much fuel my car dumps into the oil upon startup.

After letting the engine sit all night, I took a pre-experiment test sample (to ensure no fuel was present) then I started my engine one, two, and three times, sampling after each event. The results were surprising. So surprising, in fact, that I re-ran this test two more times to make sure my results were correct.

The pre-experiment test sample revealed a flashpoint of 360ºF (fuel at <0.5%). Okay, good. No measurable fuel was present, which is exactly what I was hoping for since I’d taken the highway route home the night prior.

After one engine start, the flashpoint read 385ºF. Wait a minute. That’s higher than the pre-sample, so there’s definitely still no measurable fuel present. Okay, maybe that was just an anomaly.

I started the engine again (for a total of two engine starts in a row). The flashpoint measured 380ºF. That meant the flashpoint was heading in the expected direction (lower flashpoint = more fuel), but still, the flashpoint wasn’t low enough to show any significant fuel.

After the third start in a row, the flashpoint read 375ºF, which was again lower (and heading in the expected direction), but not low enough to show any measurable fuel. So all four of my samples from that morning had the same fuel measurement: <0.5%.

I was stumped. I was so certain I’d have some fuel in my oil! So I ran the test again and the same thing happened: no measurable fuel present in any of the samples. I re-ran the same exact test once again, and once again got similar results.

I decided perhaps my Kia was just very good about keeping fuel out of the oil, so I took my husband’s car with a supercharged 2.0L Ecotec engine for a day and tried the same test. The results? Same thing: no fuel, with slight fluctuations in the flashpoint.

Then I had an “a-ha!” moment. Maybe the fuel just wasn’t getting a chance to seep down past the rings into the oil. I had been sampling immediately after starting, so maybe that’s why no fuel showed up. So I ran the test again, only this time I let my engine sit overnight after the three starts.

In the pre-experiment test, the flashpoint measured 370ºF, showing <0.5% fuel. I started my engine three times and immediately after the third start, the flashpoint measured 360ºF, which was lower but still not low enough to show any measurable fuel.

Then I let the engine sit all night and sampled before work in the morning. That test revealed a flashpoint of 365ºF; still no measurable fuel. By this point I wanted to find a brick wall to repeatedly press against my forehead in a semi-violent manner. I was frustrated, confused, and worried that I’d have nothing to write about.

I suppose if we wanted to get into semantics, we could talk about the slight differences in flashpoints as showing some fuel, though it takes a 20ºF drop in flashpoint (for gasoline engines) to show 1.0% fuel dilution. So that means the 5ºF drops in flashpoint I’d noticed likely show just 0.25% fuel.

Does starting cause fuel? Perhaps. I did find slight dips in the flashpoint, though as I’ve mentioned, 5ºF isn’t enough to show any serious contamination. Maybe four starts would have given me enough of a drop in flashpoint to get a decent amount of fuel in the oil, but really, who starts their engine four times in a row? Honestly, who starts their engine even three times in a row on a regular basis? I wanted these to be relatively real-world scenarios, so I couldn’t justify four starts in a row, and I figured three was pushing it.

Idling

I couldn’t get any serious fuel to appear in my oil from starting the engine, so I figured I’d try idling. For a week, I drove the same highway route home, let my engine sit all night, then in the morning I’d take a pre-experiment sample (to confirm no fuel dilution was present to begin with), and then I’d sample after a certain number of minutes of idling.

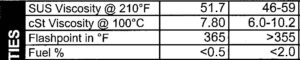

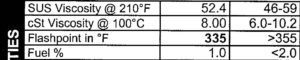

I tried a five-minute idle; no measurable fuel. The next morning, I idled for ten minutes and this time I had more success: 1.0% fuel had accumulated in the oil. You know, for someone trying to get fuel contamination in my oil, 1.0% isn’t an impressive amount, but it’s more than I’d gotten before. I figured I was on to something with the idling, so I tried 15 minutes the next morning, but much to my dismay only 0.5% fuel turned up. After 20 minutes of idling, still only 0.5% fuel.

Does idling cause fuel dilution? It would seem so, except that there’s a cut-off point in there somewhere. This is just hypothetical, but maybe after ten minutes the engine heats up enough that it either starts cooking off the excess fuel dilution or it just stops pumping in extra fuel. I’m not even sure one of those is the answer, but it’s the best guess I can come up with.

Shopping for science

With my newsletter article deadline quickly approaching, I had to come up with one last-ditch effort to get a bunch of fuel in my oil. Think of this as Custer’s Last Stand (except with less bloodshed).

For one afternoon, I vowed to do everything “wrong” in order to get as much fuel as possible in my oil. I was going to run a bunch of errands, idle my engine excessively, make frequent starts and short trips. The best way I could think to do this (without just circling around my block several times in one afternoon) was in one, massive shopping trip.

I did about 40 minutes of highway driving Saturday evening then let my Kia sit all night. Sunday after church (we took the other car to ensure the consistency of my results), I went on my scientific shopping trip.

Here’s the summary of my trip. I spent a total of about six hours shopping Sunday afternoon. In those five hours, I started my engine seven times, idled at the ATM for about 2 minutes and traveled a grand total of 6.4 miles. The longest drive was from my last stop to home, which was about 2.5 miles.

I spent a fair amount of time at each stop in hopes that my engine would stay relatively cool (so as to not burn off fuel). When all was said and done, I left my engine sit overnight and sampled in the morning before work. The flashpoint read 375 ºF: <0.5% fuel.

Usually, I’m fairly good at things when I put my mind to it, but when it comes to getting fuel dilution in my engine oil, I failed. Then again, if you’re going to fail at anything, this is a good thing to fail at.

What happened?

So why couldn’t I get any serious fuel dilution? I have a couple of ideas. First, I think my Kia is just too smart. It has an on-board computer that senses things like ambient temperature, engine temperature, and elemental composition of the exhaust gas, and it uses these things to calculate the exact amount of fuel it needs to operate most efficiently. So my engine never puts in more fuel than it needs, and therefore that fuel doesn’t end up in my oil.

Second, I think ambient temperature probably has a lot to do with it. I did most of my testing in May and June in temperatures were almost always above 70ºF. We tend to see more fuel in the winter months, and I suspect that if I’d done my testing in the winter, I might have had different results. I’ve heard that on a cold day, fuel from the air/fuel mixture will condense on the cylinder walls almost instantaneously. Those beads of fuel will sit on the cylinder walls for a brief moment until the piston rings scrape that fuel down into the oil. Maybe I’d get more fuel in my oil in winter, but I’m not sure I’m willing to do these experiments in the dead of winter in the name of science. If I do, you’ll hear from me again and I’ll let you know what I find out.

Does the fact that I couldn’t get any fuel in the oil mean that idling, city driving, and frequent starts do NOT cause fuel dilution? We don’t think so. In some cases these things can cause fuel contamination, especially in carbureted engines.

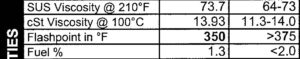

We saw it with our own eyes several years ago, when an intern did a similar experiment out in the parking lot. He took a sample from his 1978 Ford pickup truck when it was cold, and that oil had no fuel in it. Then he started the engine and took another sample right away, and presto! Fuel contamination at 1.3%. So start-up can indeed cause fuel to enter into the oil, but newer engines may be better at avoiding excessive contamination.

We saw it with our own eyes several years ago, when an intern did a similar experiment out in the parking lot. He took a sample from his 1978 Ford pickup truck when it was cold, and that oil had no fuel in it. Then he started the engine and took another sample right away, and presto! Fuel contamination at 1.3%. So start-up can indeed cause fuel to enter into the oil, but newer engines may be better at avoiding excessive contamination.

Since fuel often comes and goes, we still believe operational factors are likely sources for fuel dilution, though perhaps injector problems are responsible for more of the fuel we see in new engines than we originally thought.

Now here’s the big question: if fuel is present at 2.0% in your sample, does that mean you have a problem? Not necessarily. Just because my Kia didn’t produce fuel dilution doesn’t mean your Honda, Ford, GM, Volvo, or other engine won’t. Every engine operates a little differently and uses a different calculation to figure out how much fuel to spray into the cylinders. Some engines tend to run a little richer for some reason or another.

Of course, if your engine doesn’t have an on-board computer, you won’t have the opportunity to benefit from its fuel-reducing powers, so fuel may be more prevalent in your samples. It should be noted that I didn’t have the opportunity to test a carbureted engine or a diesel engine, which would almost certainly render different results. So I can’t say what’s normal for those types of systems.

So how do you know if fuel is a problem? There isn’t a one-size-fits-all answer. Whether or not fuel is a problem depends on your circumstances. Some engines will always see some fuel dilution because of the operation they see or the type of engine they are. Turbo and supercharged engines, for example, have higher compression, which means more blow-by, and we sometimes see that raw fuel blowing past the rings. In small amounts, that can be fine. In larger amounts, it’s probably not.

If you start to notice that fuel is increasing wear or diluting the additives in your oil, that can be a sign that fuel’s a problem. If you notice increased wear and lingering fuel dilution, it may be time to get the fuel issue taken care of. Finally, if you notice your engine is “making oil” (the oil level seems to be rising on the dipstick), you might have a fuel system problem. I can tell you this: if you have a Kia 2.4L 4-cylinder engine and you find fuel at more than 1.0%, you may have a problem. You might also have an e-mail in your inbox from me asking you for pointers.

Related articles

How Often Should You Change Your Oil?

Every 3,000 miles is a thing of the past!

Rebuilding a GM 350 Engine

A 1983 GM engine gets some love

The Fuel Experiment

We experiment with fuel contamination so you don't have to!

How Often Should I Sample?

Every oil change? Every year?