This Ain’t Your Daddy’s ATF

From lifetime oil to CVTs, transmissions are changing

It’s been a while since we wrote about transmissions: how they work, the differences between manual and automatic transmissions, and what transmission oil looks like. Since that time, a fair amount has changed in the transmission world, both in the machines themselves and the oil they use, as well as our knowledge on the subject. “Lifetime” transmission fluids are pretty common now, as are CVT (continuously variable transmission) units. Transmission oil has changed too, with certain transmissions requiring special oils, so we thought it was high time for an update.

Learning how newer transmissions work

While manual transmissions are fairly simple machines that tend to run forever, automatic and CVT transmissions are more mysterious in how they work.

When we hire new report writers, training them on the ins and outs of transmissions and transmission oil takes quite a bit of time and a lot of internet searching to find good videos on how they work.

From time to time, a little “hands-on” training is required. Over the years we have purchased several different junk-yard transmissions and torn them down, looking to see how they work and where the metals we see might be coming from.

Dissections like this tend to be a lot of fun and we learn quite a bit from the process. They are also low-stress affairs because we don’t have to worry about putting anything back together.

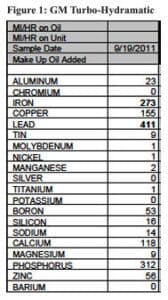

One of the first transmissions we took apart was a classic GM Turbo-Hydramatic, which was used in GM cars and trucks from the 1960s to 1990s (see Figure 1). It was always a bit of a mystery as to where lead came from in that type of transmission and it turns out, it’s a bearing metal, just like what used to be common in engines.

It was always a bit of a mystery as to where lead came from in that type of transmission and it turns out, it’s a bearing metal, just like what used to be common in engines.

Nowadays, aluminum is the bearing metal of choice for most engines and transmissions, and that makes our lives a little harder when writing reports because aluminum can be from other areas too.

Shaking up the world of transmission oil

For years and years, automatic transmissions like this didn’t have any special oil requirements. They all pretty much ran on Mercon/Dexron ATF (automatic transmission fluid). This is a light oil (normally 10W) containing only a little boron, calcium, and phosphorus as additive. It was also traditionally dyed red, so when it started leaking you knew where it was from.

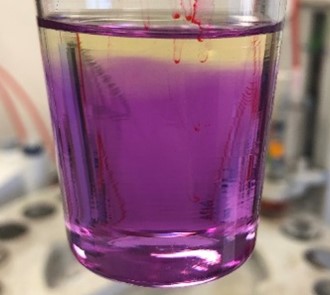

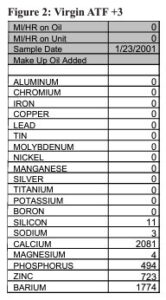

Then in the early ’90s, Chrysler came out with ATF+3 and this shook everything up in the transmission world. This oil is still a 10W in viscosity and still has a red dye, but the oil additives were significantly different than anything we’d seen before (or since) — see Figure 2.

This oil and the transmissions they were used in worked just fine; problems only came about when a different type of ATF was added by mistake. This caused the transmission to burn up because the new oil’s additive package wasn’t correct. We started getting a lot of calls about this type of transmission where the mechanic thought someone added engine oil to it, but it was actually ATF that had just turned brown due to excess heat. So this problem has been around for a while, but for the longest time it was limited to Chrysler products — until CVT transmissions hit the market.

CVT transmission & oil

This type of transmission is also known as a shiftless transmission and is similar to what you might find on a snowmobile. It has a steel belt connecting two sets of cones. Both cones can change their diameter, which essentially allows the unit to have an infinite amount of “gear ratios” available.

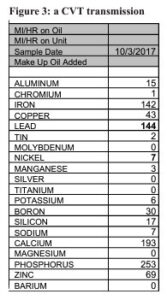

We dissected one of these a few years back (see Figure 3) to see what made them tick. These units tend to work well but are extremely sensitive to the oil they use.

Again, most of these oils are light in viscosity (10W) but they have a unique additive package, and they also tend to be dyed blue or green to differentiate them from the typical red ATF that many transmissions run. Unfortunately, we see a lot of samples from CVT transmissions where the wrong oil has been used. This causes the units to burn up because the belt driving the cones relies on the oil’s additives to maintain the correct friction.

Again, most of these oils are light in viscosity (10W) but they have a unique additive package, and they also tend to be dyed blue or green to differentiate them from the typical red ATF that many transmissions run. Unfortunately, we see a lot of samples from CVT transmissions where the wrong oil has been used. This causes the units to burn up because the belt driving the cones relies on the oil’s additives to maintain the correct friction.

“Lifetime” transmission oil

The early 2000s brought about the rise of “lifetime” transmission fluids and also sparked a lot of debate about what that meant and how it could even be possible.

The idea that there is a fluid in your vehicle that never needs to be changed goes again some people’s religion, and I’ll admit it was a little difficult to understand at first. My 2003 Volkswagen Passat had that type of transmission, and it didn’t even have a dipstick, so I couldn’t run any tests on it to verify that the fluid was in good condition. Still, the lifetime of that transmission for me was 91,000 miles (that’s when I sold the car) and I will admit I never had any problem with it.

Still, it just seems wrong not to change the transmission fluid every now and then. Up until that point, I had always changed the transmission fluid in my cars and trucks, but after a lot of thought on the subject, I’m starting to wonder if that’s really necessary. For a lot of vehicles, changing the transmission oil could cause more problems than it could help, due to the possibility of the wrong oil being used to refill it.

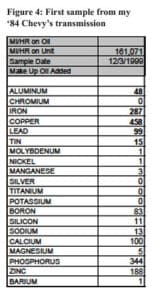

Also, it’s quite possible that the wear accumulation in transmission oil doesn’t have the same abrasive affect that it does in engines. To demonstrate this, I’d like to show you the first sample from my 1984 Chevy Custom Deluxe K20 pickup truck (see Figure 4). You might remember this truck from such classic newsletters as “Rebuilding a GM 350”, “ZDDWhat?”, and “The Renuzit Experiment.”

When I first bought this truck in 1999, I took a sample from the transmission and was sickened by the amount of metal that was present (see B30211). I immediately changed the oil several times myself and then got in the habit of having a shop change it every year or so. Still I expected that thing to give up the ghost at any moment and just hoped I wasn’t far out of town when it happened. The funny things is, it’s still running to this very day (and is still going as of June 2024).

Now maybe all of the oil changes that I did early on made that possible, but at this point I’m leaning towards another explanation: transmissions can make a lot of metal and still be perfectly normal.

I think that’s because the oil in transmissions has a significantly different life than engine oil does. Transmission oils are mainly used as a hydraulic fluid to shift the gears though an ingenious invention called the valve body. This is like a circuit board that uses oil rather than electricity, and apparently the cleanliness of the oil doesn’t affect its operation.

Sure the oil also lubricates the gears, but as far as an oil’s jobs go, that’s one of the easiest things for it to do. The oil really doesn’t even have to be very clean to do that job well. So if the cleanliness of the oil isn’t that critical, then lifetime transmission oils start to make sense.

The transmission killer extraordinaire

It has been our experience that what kills most transmissions is heat. If the oil gets too hot it actually loses its viscosity and is no longer able to lubricate properly, which in turn causes more heat and eventually a total failure.

So in closing, if you have a “lifetime transmission oil,” rest easy — there is probably no need to worry about changing it. You’ll likely get sick of looking at the vehicle before the tranny dies. However, if you notice your transmission starting to leak oil, that’s the time you’ll want to have it fixed because its lifetime will quickly expire if you don’t. Just be sure they put the right oil back in!

Related articles

A New Wave

Saying goodbye to my 1984 Chevy

TBNs & TANs: Part 2

Determining how heat affects the TBN and TAN of the oil

Finishing the RV-12

The last article in our series on finishing the RV-12

In the Thick of it!

Five cities, five days, 5000+ cars: the 2024 Hot Rod Power Tour!